How Chinese fishermen saved British POWs from a torpedoed WWII warship

Imagine for a moment that you are a prisoner of war, held by the Japanese during World War II. You and 1,815 other PoWs have been herded into the overcrowded, lightless holds of a former cargo liner to be transported to an uncertain fate.

And then a torpedo hits. Slowly, agonizingly, over the course of 24 hours, the ship starts to list and sink. Your captors batten down the hatches, sealing you in, and you hear them leave the ship in their hundreds.

When you try to escape – surely the only option – you see your colleagues shot dead by a few remaining guards left behind. Eventually, the guards are overpowered. With the ship going under, you jump into the water – and find yourself fired on again by Japanese boats.

One of the last photographs taken of the sinking Lisbon Maru. /CGTN Europe

You see your comrades-in-arms killed helplessly. You see some, unable to swim, go down with the boat. Others swim out to sea, preferring to drown alone than be shot. And then, from nowhere, comes a fleet of tiny Chinese fishing boats. Grabbing the survivors and relaying them to shore, the fishermen save hundreds of lives.

If it sounds like a script from a film, it is – The Sinking of the Lisbon Maru. But it's a documentary, a true story, and one perhaps more fantastic than any Hollywood potboiler.

"There's no such thing as friendly fire." So says William Beningfield, one of the longest-living survivors of the Lisbon Maru, in the documentary.

For wartime service personnel to be shot at is a terrible inevitability, but to be blown out of the water by your own side counts as tragedy. The 1,800 Allied troops on the Lisbon Maru were torpedoed by the submarine USS Grouper; with the cargo ship being armed and not, as expected by the Geneva Convention, marked as a PoW transport, it was a fair target.

Held in three separate cargo stores, the troops already faced horrendous circumstances – some died from diphtheria, while other contagious diseases spread at will. The torpedo strike ensured that one hold started to fill with water, at which the Japanese lowered a hand-pump and ordered the prisoners to pump for their lives; in the stifling airless heat and without food or water, even the fittest of military men could only last a few strokes before collapsing with exhaustion, and all men well enough took their turns in a desperate attempt to keep the ship afloat.

When a group of men finally broke out – with the first wave led by Lt HM Howell, who shortly before the torpedo struck had been regaling his fellow prisoners with his tales of surviving two previous shipwrecks – and overpowered the remaining guards, they helped their comrades out of the other holds.

Tragically, however, the ladder from the third hold broke, leaving hundreds of men to their fate. Several witness statements corroborate that among the last sounds heard from the hold was a group singalong of the stage favorite It's a Long way To Tipperary.

Those who made it to deck, and weren't shot by the remaining guards, discovered their captors had left only four lifeboats and for life rafts for the 1,816 prisoners. Many simply jumped into the sea – some intending to swim for the islands a tantalizing few kilometers away, others simply to hope for help.

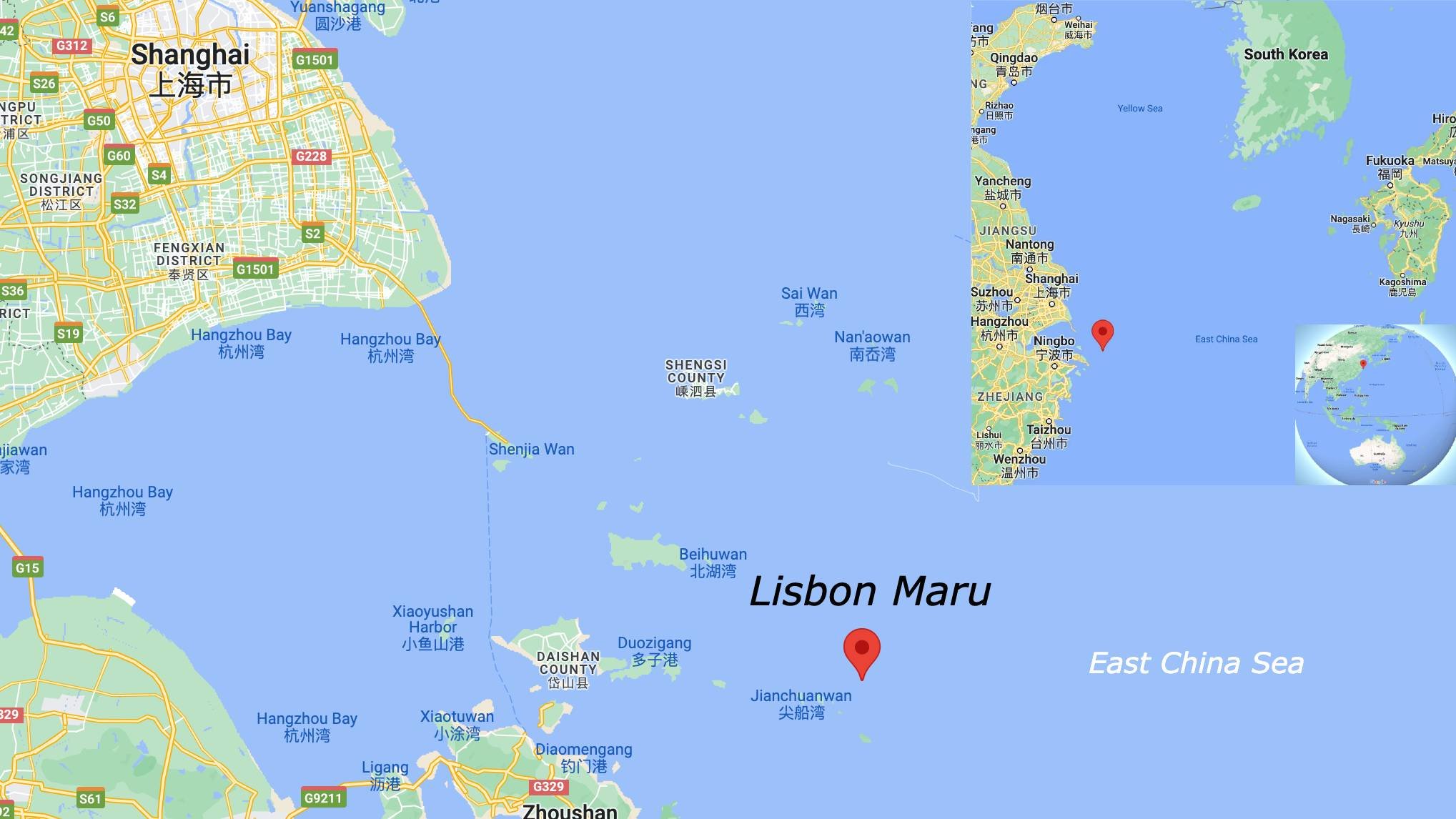

The Chinese fishermen set out in their hundreds from a nearby island in the Zhoushan archipelago in the East China Sea south of Shanghai. /Google Maps

Instead, they were fired upon by Japanese boats. Some reported that ropes were lowered from the boats, but when the POWs clambered up them, they were kicked back into the sea.

One man in the water, 2 Lt Douglas Baird of the Royal Scots, attempted suicide – first by swallowing seawater, then by stabbing himself with nails from the driftwood he was clinging to. He passed out and was plucked from the sea by a Chinese fisherman.

The fishermen, alerted by an explosion when the Lisbon Maru finally sank, set out in their hundreds from a nearby island in the Zhoushan archipelago, in the East China Sea south of Shanghai. As Susan Wilkinson, the daughter of Lisbon Maru survivor Pvt William Spooner, later recalled: "Dad had passed out when he was rescued and when he awoke, he thought he was in heaven because an angel was caring for him. It was one of the women on the island."

When the Chinese arrived, the Japanese – knowing that any further firing would be witnessed – changed tack to also rescuing prisoners from the sea. Tony Banham, author of The Sinking of the Lisbon Maru: Britain's Forgotten Wartime Tragedy, has calculated that 828 PoWs died either on board or in the water nearby; those fishermen's actions saved almost a thousand lives.

Almost 400 men were taken ashore by the Chinese, and were fed and clothed.

"I still remember the piece of turnip that a local fisherman gave me," recalled Benningfield. "It's the best food I've ever had in my life. The fishermen risked their lives to save us. They are the real heroes."

The PoWs' liberty did not last – the Japanese returned over the next few days to find them. With the exception of three who were hidden by the locals in a rocky cave, most of the men surrendered rather than risk reprisals against the Chinese who had saved their lives.

First published by CGTN Europe, 19 Aug 2023