How Kevin Keegan’s romantic return to Newcastle ended with yet more broken hearts

A decade ago today (September 4), King Kev turned his back and headed for the door marked ‘exit’ at St James’ Park, citing irreconcilable differences with Magpies owner Mike Ashley. Plus ça change…

He’d left Newcastle before. Unusually emotionally highly-strung for a player or manager, Kevin Keegan was often prone to the impulsive gesture — the on-field Charity Shield fight with Billy Bremner, the wild-eyed Fergie-prodding “I would love it” TV talkback, the England resignation in the Wembley toilets — and distraught Magpies fans were used to seeing the back of his bonce disappear over the horizon.

In May 1984, Keegan had been airlifted from the St James’ Park pitch in a helicopter, still clad in full kit, after a Thursday-night testimonial against his old team Liverpool, who were a fortnight from winning their fourth European Cup. His 28 goals had hauled a team mixing the nous of Terry McDermott with the potential of Peter Beardsley and Chris Waddle to promotion back to the top division, as promised. At 33, he was eschewing a final top-flight tilt, hanging up his boots and pledging never to become a manager.

Eight years on, he was parachuted (this time not literally) back in to replace hapless manager Ossie Ardiles and save Newcastle from a first-ever relegation to the third tier. Within a month he’d walked out — “It’s not like it said in the brochure” — but new chairman Sir John Hall waved an open chequebook and over the next few seasons Keegan led the club to be, for a while, Manchester United’s main challengers at the summit of English football.

That reign ended abruptly on January 8, 1997. Less than three months after his side had demolished Alex Ferguson’s champions 5–0 on Tyneside, Keegan suddenly resigned. Newcastle were fourth, world-record summer signing Alan Shearer was scoring metronomically, but the manager walked out on a 10-year contract, saying: “I’ve taken the club as far as I can.” Folk wept on the streets; it would later be described by chairman Freddy Shepherd as “like losing a family member”.

…aaaaand we’re back in the room

Keegan was out of football for eight months before returning via Fulham, then England and Manchester City. He resigned the Maine Road hotseat in March 2005 after informing chairman John Wardle of his intention to retire that summer. As late as October 2007 he doubted he would return to management, but once again Mighty Mouse couldn’t resist when the Bat-Signal went up over St James’ in January 2008.

Not for the last time in his career, Sam Allardyce’s footballing methodology had proved anathema to the inherited belief system of a club’s fan base. Keegan’s swashbuckling attitude brought cavalier football to a Cavalier city: during the Civil War, Newcastle had been a Royalist outpost — the victorious Cromwell subsequently helped Parliamentarian Sunderland loosen Newcastle’s monopoly on coal trading. Allardyce’s perceived Roundhead roboticism was never an easy fit for fans reared on the glorious near misses of Tino Asprilla and Mirandinha.

Hence the Restoration of King Kev. However, it wasn’t quite the inevitable romantic reacquaintance. Mike Ashley had tried to hire Portsmouth’s Harry Redknapp, while other names in the hat included Blackburn’s Mark Hughes, ex-Liverpool boss Gerard Houllier and Didier Deschamps, who was halfway between his World Cup wins as player and manager but recently turfed by Juventus. Even Alan Shearer, 37 and entirely experience-free, was considered before being told this was no job for a newbie.

Meanwhile, the team was suffering. Any notion that the absence of Allardyce would automatically remove the shackles was comprehensively demolished when caretaker Nigel Pearson oversaw a 6–0 capitulation at a gleeful Manchester United.

Keegan’s return on Wednesday, January 16 was greeted with surprise everywhere but Newcastle, where the feeling was more like VE Day. BBC Radio 5 Live’s football correspondent Mike Ingham summed it up: “It’s a great soap opera. Locally they will be in raptures but outside it there may well be bewilderment.” The incoming manager arrived in the stands during the first half of an FA Cup replay against Stoke, a 4–1 win adding to the party atmosphere.

It didn’t last. His first game back on the touchline was against Bolton, managed by ornery Allardyce-lite Gary Megson. They pooped the party by holding out for a 0–0 draw, but Jussi Jaaskelainen didn’t have a save to make. Two visits in a week to Arsenal, including in the FA Cup fourth round, yielded twin 3–0 defeats. The Second (Managerial) Coming had promised fireworks, but this was a damp squib.

Ins and outs

Upon his return, Keegan had been under no illusions as to the size of his task. Worryingly for Ashley, his new manager had made it publicly known that “It won’t be easy: we haven’t got a huge squad”. Indeed, when Allardyce was called in to get the bullet, he had expected the meeting to be an announcement of another completed incoming transfer. But having watched the last manager spend £25m over the summer, the owner wasn’t about to bankroll another spree.

The only incomings under Keegan before the January window closed were inconsequential teenagers: Allardyce legacy signing Tamas Kadar (who would go on to make 18 league appearances in four-and-a-half years on the payroll), Italian forward Fabio Zamblera (zero appearances in three-and-a-half years) and Swedish goalkeeper Ole Soderberg (zero appearances in four years), with 33-year-old Senegalese free agent Lamine Diatta following in March on a short-term deal.

By that time, it had become very clear that Keegan was not in full control of signings. On January 29, with Jim White excitedly ironing his yellow tie, Ashley appointed a slew of suits to act as managerial middlemen. Dennis Wise was the big-name Executive Director of Football, but also incoming were Tony Jimenez and Jeff Vetere.

Jimenez, a Brixton-born Cyprus-based Spaniard with an executive season ticket at Chelsea, was to become Vice President of Player Recruitment. Affable with a bulging contacts book, the property millionaire was a longtime friend of Wise and Ashley, and a surprise appointment to many in the business. “I’m amazed that he’s been entrusted with player recruitment,” said one agent. “He knows nothing about football.”

The same couldn’t be said about Vetere, who certainly had the chops. A former Luton apprentice turned quadrilingual UEFA A-licensed coach, he had worked his way up the backrooms from Rushden & Diamonds via Charlton and West Ham to Real Madrid, from whence he was lured to be Newcastle’s Technical Co-Ordinator — in effect, the chief scout.

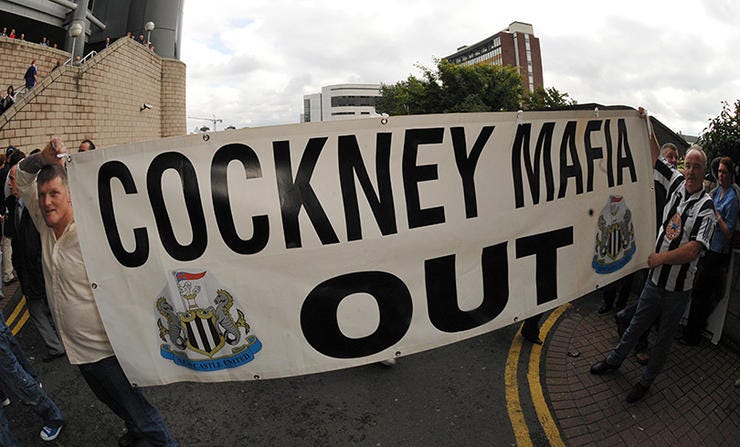

Clearly, Vetere knew his onions but Keegan was less than pleased by the phalanx of incomers. Ashley wanted what was then parochially known as a “continental-style” set-up in which the manager was little more than a head coach, cheerleader and chief scapegoat. Keegan was particularly unhappy that Wise — whom he had called up as a thirtysomething player to 12 England squads, giving the little aggro-engine eight of his 21 caps — would be in charge of transfer dealings, using Jimenez as the smooth-talking go-between to capture Vetere’s targets. To Ashley, it made perfect sense. To the Newcastle fans, their club was being overrun — and their hero undercut — by a ‘Cockney Mafia’.

Such was the surprise that King Kev’s second spell on the throne was almost cut short within a month. Ever impulsive, the returning hero resigned upon hearing of his new middle-management team, and it took considerable persuasion from the owner to talk him out of it.

Ashley is a difficult man to side with, particularly in discussions with Newcastle United fans and certainly in comparison to a folk hero like Keegan, but his reasons for wanting oversight on the manager’s recruitment weren’t limited to mere parsimony. This is the gaffer who, in early 1996 with Newcastle’s title charge threatened by a wobbly defence, had signed David Batty with the idea of turning him into a ball-playing centre-back.

Clearly, the man needed guidance, and Ashley had no intention of imitating Sir John Hall with a carte blanche chequebook. The owner had been the sort to gamble on which raindrop would reach the bottom of the window first, but he wasn’t going to stake his own money on the optimistic whim of a mere manager.

Even so, Ashley knew that forcing the messiah into exile would be a horrendous own goal, and he impressed upon Keegan how the new structure would allow him to focus on his prime asset: leadership. King Kev was to be a leader of men, more suited to inspiring on the training pitch and in the dressing room than dealing with agents and fixers.

Onwards and… downwards

Perhaps encouraged to think of the moist-eyed children who would gather outside St James’ if he left once again, Keegan agreed to stay on. He had been managerially emasculated and unable to augment his squad, but the ball rolls on and there was a derby to play.

Middlesbrough came to St James’ and conceded within four minutes, with Keegan’s new captain Michael Owen stabbing home his first goal since October 22 — except Mike Dean disallowed it, reasoning incorrectly that Mark Schwarzer must have been fouled to have dropped the ball. Fifteen minutes later Owen bagged again but was again denied by the officials, who’d this time accurately noted that Emre’s cross had gone out of play.

Owen did break his duck — and score the first goal of Keegan’s second reign — on the hour to put Newcastle in front. Never backwards at going forwards, the manager promptly threw on James Milner for Emre and Mark Viduka for Alan Smith, and watched as Boro equalised in the 87th minute. It might have got worse had the officials not ruled out Jeremie Aliadiere’s late ‘winner’ for offside.

What might have been a bold win almost turned into a calamitous collapse, and Keegan’s luck wasn’t turning. The Boro draw was followed by four defeats on the bounce: 4–1 at Villa, 5–1 at home to Manchester United, 1–0 at home to Blackburn and 3–0 at Liverpool.

By mid-March, Keegan’s first two months back at the ranch had yielded no wins in eight games, three goals scored to 20 conceded, and a slide down the league from 11th to 14th, just four points above the drop zone. By inevitable comparison, Allardyce’s final eight games had included two wins and three draws, seven goals scored and nine conceded.

Questions were now being asked whether Keegan’s tactics and managerial acumen had been left behind in the Premier League’s decade of constant improvement, but a draw from behind at fellow drop-dodgers Birmingham kicked off a seven-game unbeaten charge. They won home six-pointers against Fulham and Reading, enjoyed a 4–1 triumph at Juande Ramos’s wildly inconsistent Tottenham and revelled in a 2–0 home win against Sunderland.

Resetting expectations

The turnaround helped hoist Newcastle away from trouble to finish in 12th place, a rung below where they were when they axed Allardyce. More notably, by the end of the season there had been a downturn in optimism, notwithstanding the spring surge. Again, the emotion stemmed from Keegan.

On May 5, in their final home game of a mixed season, Newcastle lost for the first time in almost two months, 2–0 to Chelsea. Experiencing their own renaissance under Jose Mourinho’s lugubrious successor Avram Grant, the Blues had collected 73 of the last 90 available points to push the title race to the last weekend of the season, and Keegan could only press his nose up against the confectioner’s window. His press conferences started to sound like a funeral wake for his club’s chances of competing with the new mega-rich elite.

“I know people might be disappointed by me saying we might not win the league, but there would be a real danger of me being whipped off to the nuthouse if I started saying that,” Keegan said. “There is a big gulf and it has been well documented, not just by myself but by many, many other people in the game whose opinions are respected… Maybe the owner thinks we can bridge that gap — but we can’t.”

This was not the rabble-rousing, sunshine-radiating optimist Ashley thought he had hired. Contract extension talks with Keegan over the summer generated the usual amount of positivity designed to sell season tickets, but the manager was dismayed that Michael Owen wasn’t being offered an extension on the four-year contract he’d penned in August 2005.

Signed under previous ownership, Owen’s deal was costing Ashley £110,000 a week, and the owner wasn’t sure he was getting full value for money. As if the striker’s regular muscular problems weren’t enough of a concern, Owen missed all of Newcastle’s summer 2008 pre-season with mumps.

Furthermore, Newcastle needed a substantial rebuild, starting with Keegan’s blind spot: defence. The Magpies had conceded 65 goals, a total topped only by relegated Reading and disastrous Derby. In came Fabricio Coloccini and Sebastian Bassong, but Keegan was hardly likely to be satiated with the calibre of forward players hired. True, Jonas Gutierrez would easily recoup his £2m fee by making 200+ appearances, but £2.5m Liverpool export Danny Guthrie didn’t justify Keegan’s comparisons to club forebears Rob Lee and Paul Bracewell.

End of the road

Moreover, with something like £15m spent on incomings and a lot less recouped from sales, Ashley was getting itchy. So was James Milner, who had asked for a transfer: “I knew offers had come in over the summer and the club ad turned them down. Their valuation of me wasn’t reflected in the deal I was on.” Aston Villa, who had just finished sixth (and would do so for the next two seasons), shelled out £12m on August 29.

A brave-faced Keegan described the deal as “win-win”: “James has got a fantastic move and we have got some more money in the pot, should we choose to use it in this window or the next. I did want to keep James but there comes a point when a deal is right to do.

“I’m convinced that despite the fact that it won’t look a positive move to our fans at the moment, I think what will happen over the next two or three days will be positive for the future of this club.”

It didn’t quite turn out that way. Within a week, Keegan was gone. Although he wore a painted smile, he felt the club had sold him short by claiming they could replace Milner with Bastian Schweinsteiger. In the event, chief fixer Jimenez asked the manager to ring his old friend Karl-Heinz Rummenigge at Bayern; Keegan did so and discovered that Newcastle had offered a derisory €5m, literally laughed at by Bayern.

By deadline day, Monday September 1, Newcastle were inviting offers for any and all first-team players, up to and including Owen and Joey Barton. In the event, there were no further departures, but it was incoming business that led to Keegan’s departure. The manager had dropped broad hints about two or three exciting signings, but the best the suits could provide was £5.7m Deportivo frontman Xisco.

Meanwhile, Uruguayan midfielder Nacho Gonzalez had been signed by Valencia and immediately farmed out on loan to Newcastle, apparently without Keegan’s knowledge — let alone assent. It later emerged that the deal was “a favour to two South American agents”, in order to get first dibs on the best young talent from that continent.

Coupled with the attempts to sell his best players and the risible failure to sign Schweinsteiger, the manager felt he had no option but to leave.

Aftermath

Even that became its own long-running farce. As early as Monday, word leaked that Keegan had resigned, quickly denied by the League Managers’ Association. Hundreds of Magpies fans descended upon St James’, calling for Ashley and Wise to resign, as intense negotiations continued behind the scenes. On Tuesday, the club issued a statement insisting that Keegan had not been sacked, but by Thursday the manager acknowledged that he had indeed jumped — for the third time.

“I’ve been left with no choice other than to leave… I’ve been working desperately hard to find a way forward with the directors, but sadly that has not proved possible,” he said in a statement. “It’s my opinion that a manager must have the right to manage and that clubs should not impose upon any manager any player that he does not want.”

With artless lack of grace, the club responded on Saturday, September 6 via a website statement. “It is a fact that Kevin Keegan, as manager, had specific duties in that he was responsible for the training, coaching, selection and motivation of the team… It is a fact Keegan was allowed to manage his duties without any interference… It is a fact that Kevin Keegan worked within that structure from 16th January 2008 until his resignation… It is a fact he agreed not to talk to the media in relation to the acquisition or disposal of players… ”

With the Premier League on an international break — Keegan’s old side England were in Andorra opening their 2010 qualification — the spat dominated the agenda, and football’s old guard sensed another long-term shift in the dynamics of the game.

Former FA executive director David Davies took refuge in scorn: “I think it’s a really sad thing that football is without Kevin Keegan again, and I do ask about a game that can be without people like Kevin Keegan. Having said all that, he is something of an old-fashioned manager. He actually believes, having been brought up by the likes of Bill Shankly and played under Lawrie McMenemy, that managers should manage, and they should have the final say on who their players are.”

Perhaps the saddest observer was Sir Bobby Robson, by now 75 and recently confirmed to have terminal lung cancer.

“The breakdown between the different job titles has left Newcastle in disarray and it is time for Ashley to sort it out,” pleaded the avuncular Magpies legend. “The owner or chairman is the most important person at a football club, the manager is second and everyone else third. If a director of football doesn’t have the blessing of the manager, it doesn’t work… no manager worth his salt is going to take the Newcastle job with the current set-up.”

Sadly for Sir Bobby, he was right. By the time the cancer killed him in July, Newcastle had been through four more managers — and been relegated.

What happened next?

On Friday 12 September, Kevin Keegan met Mike Ashley again in an attempt to reach a workable compromise. It didn’t work, and on Sunday 14, Ashley put the club up for sale. As late as October, the LMA were saying that Keegan could return if the structure was changed. But Ashley couldn’t find a satisfactory buyer and withdrew the sale on December 28.

As predicted by his England predecessor Graham Taylor, Keegan sued Newcastle for constructive dismissal. An October 2009 tribunal ruled in his favour, awarding him £2m. Keegan has never returned to management.

Chris Hughton took over as caretaker until September 26, when Newcastle appointed Joe Kinnear as interim manager. The former Wimbledon boss started spectacularly with an expletive-laden, media-threatening press conference, and only lasted until February 7, when he was admitted to hospital with heart problems.

Hughton was recalled as caretaker until April 1, when — with Newcastle in the bottom three — Alan Shearer was appointed interim manager for the final eight games of the season. Shearer briefly got the club above the dots with a win over Middlesbrough but otherwise only managed two draws and five defeats, condemning the club to the drop.

Dennis Wise left Newcastle on April 1, the same day Shearer took over. “Mike sacked me,” he later said. “It has had a damaging effect on my career and has not been fantastic for me.” Indeed, Wise hasn’t had a frontline football job since Newcastle, but has kept himself busy with media, hospitality and appearing on I’m a Celebrity, Get Me Out of Here and The Crystal Maze.

Tony Jimenez (pictured below) left Newcastle in early October when Ashley put the club up for sale. In January 2011, along with Michael Slater, Jimenez took control of Charlton Athletic and immediately sacked Phil Parkinson. He sold out to Roland Duchâtalet in 2014. By then Wise had sued Jimenez for £500,000 in damages over a golf-course property deal in France; the same deal was at the heart of a 2017 litigation in which Ashley sued Jimenez for £3m.

Jeff Vetere spent two years at Newcastle before becoming Gerard Houllier’s chief scout at Aston Villa in November 2010. The following June he returned to Jimenez-run Charlton as technical director. He later worked for Fulham, the Premier League and Birmingham, the latter as Harry Redknapp’s Director of Football.

Xisco scored on his debut, against Hull, but never repeated that trick in 10 further appearances over four-and-a-half long, expensive seasons.

Nacho Gonzalez made two substitute appearances for Hughton’s Newcastle — both in losses — before an achilles injury ruled him out for four months. He later played in Greece, Spain and Belgium before returning to Uruguay. Despite the promise of first choice on promising youngsters, Newcastle didn’t sign another player from South America until August 2014, when Facundo Ferreyra arrived on loan from Shakhtar Donetsk. He didn’t play a senior minute for the team.

Originally published at www.fourfourtwo.com on September 4, 2018.