Should I Worry About... A second wave of COVID-19?

What’s the problem?

Understandably, people are bored of lockdown. After months and weeks of curtailed activity and increased isolation, many are afflicted by fear fatigue – something like compassion fatigue, but instead affecting the ability to experience a healthy concern.

In the UK, lockdown was announced on 23 March, the day after a 24-hour COVID-19 death-toll of 74. The latest easing of lockdown restrictions in England was announced on 23 June, the day after a UK daily death-toll of 280.

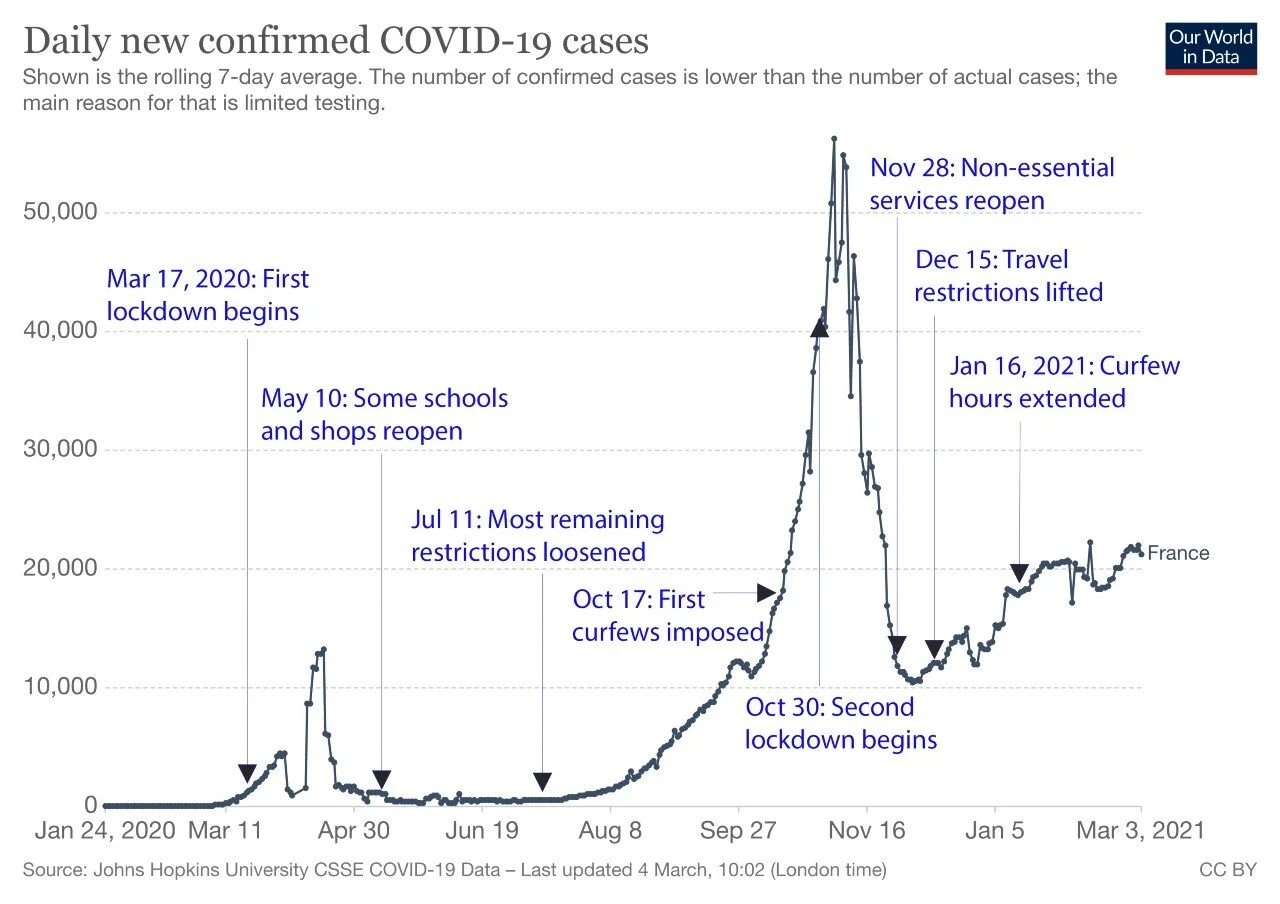

Although the overall trend is certainly downward from the pandemic's peak, many are suggesting that easing restrictions too quickly might be leaving Europe open to a fresh outbreak as people let down their guard. The day after England announced its forthcoming relaxation of restrictions, as the country basked in its hottest day of the year, some of its beaches were rammed with thousands of people flouting the recommendations on social distancing.

That prompted England's chief medical officer Chris Whitty to tweet: "COVID-19 has gone down due to the efforts of everyone but is still in general circulation. If we do not follow social distancing guidance then cases will rise again. Naturally people will want to enjoy the sun but we need to do so in a way that is safe for all."

Just as the public is understandably bored, business leaders are understandably worried. Across Europe, countries who were forced to provide huge and unforeseen healthcare and welfare subsidies are attempting to reopen and revivify economies which all but ground to a halt. On 14 June, announcing the reopening of cafés and restaurants as well as his country's borders, French president Emmanuel Macron summed it up: "We must relaunch our economy."

As lockdown restrictions are eased – albeit at different paces in different places – the sense of stepping back into the sunshine is somewhat spoiled by a large shadow: what if there is a second wave, or spike, in COVID-19 cases and deaths?

It's not a new concern: the number of Google searches for "second wave" has risen gradually in direct opposition to Europe's falling rates of new cases and deaths. And the fear of a secondary spike has brutal historical precedence: we've been here before, and it was fatal.

The first registered cases of the so-called "Spanish flu" came in Kansas in March 1918. (The virus got its misnomer primarily because the Spanish, neutral in World War I, reported the outbreak more freely than nations at war.)

That spring 1918 outbreak had relatively low mortality, but later that year – with its spread aided by demobilizing soldiers and a peace-prompted uptick in movement around Europe – the virus returned with a level of lethality unseen since the Black Death six centuries earlier. It infected half a billion people, around one in three of the planet's population, with estimates of the death toll ranging as high as 100 million.

What's the worst that can happen?

Infecting a third of the planet and killing a nine-figure slice of the population is quite impressive, and that was in a time before mass tourism and regular global business trips.

No wonder, then, that Edinburgh University's global public health professor Devi Sridhar is unlikely to be gathering the neighbors for a street party any time soon. "All countries should be worried about a second wave of this virus," she tells CGTN. "We still think there are a number of susceptible people who could still catch this virus and become ill from it."

Indeed, those countries who best dealt with the (first?) wave of COVID-19 have the biggest risk attached to a second spike. And despite the coronavirus's domination of our lives, there is a lot of room for it to grow: according to the New Scientist magazine on 17 June, "tests in Spain, Italy and England put the proportion of people infected at between 2 and 5 percent, although the prevalence is higher for densely populated cities like London and Madrid."

This raises another concern about the epidemiology of infection. If lockdowns kept the first wave concentrated in the big cities, freedom of movement could cause a secondary wave to sweep smaller towns and villages where the population tends to be older and more susceptible – and there is much lower healthcare capacity per capita, from GPs to intensive care beds.

Even survivors may not be rendered safe through their suffering: although it is hoped that a previous infection gives a COVID-19 victim the antibodies to fight off a recurrence, very little is known for certain.

"The evidence is the vast majority of people are still susceptible," said the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine's Adam Kucharski. "In essence, if we lift all measures, we're back to where we were in February. It's almost like starting from scratch again."

What do the experts say?

Outside the wilder realms of conspiracy theory and disinformation, nobody is saying there is no need to worry. Even as governments ease lockdowns, they are making clear that they can quickly revert if need be: in Germany, two districts had restrictions reintroduced after more than 1,500 workers at a meat-processing plant tested positive.

Clearly the easing of restrictions is subject to various checks and measures as epidemiologists. Spanish prime minister Pedro Sanchez struck a typical note of caution: "We must remain on our guard," he said, insisting a second wave "must be avoided at all costs."

For Devi Sridhar, the question is not whether but when a second wave will threaten to break upon Europe – and how to minimise its effects. "It is avoidable if countries are willing to do mass testing and tracing," she tells CGTN. "Keep on top of the importation of cases through watching their borders and having constant monitoring and surveillance in place until we have a better solution."

Others worry about the potential effects on healthcare providers who fought so heroically in the spring. Some have complained of PTSD-like symptoms, and the fear is a second wave could push them beyond their limits. That's why the leaders of several healthcare professions wrote an open letter in the British Medical Journal pleading for continuing infrastructure overhaul, even as the current wave ebbs down.

Read more: Medics forced to “dissociate” by trauma of COVID-19 work

"While the future shape of the pandemic in the UK is hard to predict, the available evidence indicates that local flare-ups are increasingly likely and a second wave a real risk," said the letter, co-signed by the presidents of the Royal Colleges of Surgeons, Nursing, Physicians and GPs. "Many elements of the infrastructure needed to contain the virus are beginning to be put in place, but substantial challenges remain."

Sridhar understands the economic argument for reopening but warns that it won't work if the virus spikes. "There's no way to run a successful economy when you have a virus on the loose within your borders," she says. "People won't consume, and they won't act as they were before.

"This is a very dangerous virus, one that you cannot just let spread through your populations – because not only will a lot of people die, but you'll have a lot of people who have long-term illness from it as well as really destroying your economy."

Sridhar insists the only way to keep the pandemic at bay is "to have massive diagnostic capacity, to test enough. You need to put in place regular monitoring. As your number of cases comes down, you need to watch for importation of cases: other countries [could] have much higher levels. We've seen this in East Asia: the importation of cases from Europe and North America.

"Don't take your eye off the ball. The virus is still there, at any point it can take off and set off a chain of infections that affects a lot of people. It's an exponential growth and so you don't want to dither, delay, wait and see."