On this day in the Euros, June 18: (Really) lucky Dutch break Irish hearts

Luck of the Irish? Don’t count on it. They certainly didn’t get any at Euro 88

Euro 88 was a singularly interesting edition of the quadrennial continental beanfeast. Its average attendance of 56,656 is a competition record unlikely to be beaten; its 2.27 goals per game wouldn’t be matched until the turn of the millennium; and it featured no red cards, 0–0s or even extra time, let alone penalties.

How favourably you remember Euro 88 might very well depend on your nationality. West Germany and Italy failed to live up to their pre-tournament status as favourites, falling at the semis. The English narrative arc went from embarrassment through humiliation to ennui.

Dutch delight at a debut tournament victory was intensified by that semi-final victory over the hated Germans, but there was another nation who enjoyed almost every moment — perhaps bar one sickening moment on June 18.

The Republic of Ireland was a footballing backwater whose competition qualification record was zero from 19 attempts. Despite the occasional brilliant player — Johnny Giles, Frank Stapleton, Don Givens, Liam Brady, Johnny Carey — they hadn’t ever really developed a strong team.

Jackie mines the diaspora

Then they broke with tradition by hiring their first non-Irish manager. As an England player, Jack Charlton had won the World Cup; as a manager, he had had won promotions with Middlesbrough and Sheffield Wednesday.

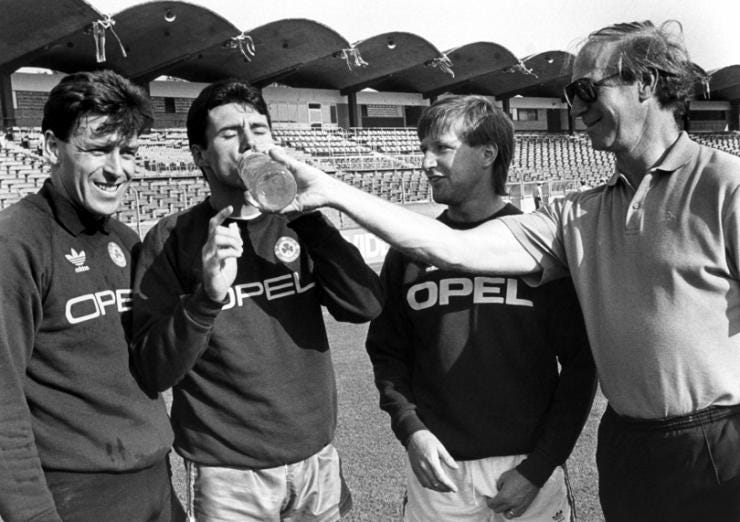

Taking charge in early 1986 after the failure to qualify for the Mexico World Cup, the genial but tough Geordie instilled his team with discipline and ruthless tactical simplicity: get the ball forward and maximise set-pieces.

Jack’s Ireland contained a disparate bunch of talents. At the back, the classy Paul McGrath dovetailed with the blunter Mick McCarthy or Kevin Moran. Skilful midfielders like Ronnie Whelan, John Sheridan, Kevin Sheedy and Ray Houghton were happy to support forceful strikers like Stapleton, Niall Quinn, Tony Cascarino and John Aldridge.

Some of these — McCarthy, Houghton, Sheridan, Aldridge, Cascarino and more — were born outside the country as part of the Irish diaspora, qualifying under the grandparents rule. They weren’t the first players to be “grandfathered in”, but Charlton was systematic and unrepentant about it.

“You want me to compete with the best in the world, I’ve got to have the f***ing best in the world,” he told the media. “And it’s not here in Ireland that I can find it, I’ve got to go to England to find it, or Scotland.

“Now, if you don’t want to do that, tell me, and I’ll f***ing concentrate on the League of Ireland and we’ll win nothing. But give me the freedom to produce results and I’ll produce results.” And he did: Charlton led them to qualification at the first attempt. The Green Army were off to Germany.

Beating the English

Enticingly, their first major tournament game was against England; deliciously, they won. Ray Houghton’s sixth-minute looped header was enough, along with the goalkeeping heroics of Packie Bonner.

It was a joyous occasion for the Irish fans, both inside Stuttgart’s Neckarstadion and back home. And it was sweet revenge for Jack Charlton, who had been turned down by the English FA in 1977.

Ireland then faced the Soviet Union in Hanover, and again took a first-half lead through a mixture of brute force (McCarthy’s huge throw) and skill (Whelan’s sumptuous hooked shot). Igor Belanov set up Oleg Protasov for the equaliser, but Ireland were joint-top of the group with one game to go.

That game was on June 18 against the Netherlands, who had lost their opener to the Russians but demolished the English 3–1 through Marco van Basten’s hat-trick. A draw would send the Irish through to the semi-finals, and 64,731 packed into Gelsenkirchen’s Parkstadion to see if they could keep the fairy tale going.

Style versus guile

Charlton was facing Rinus Michels, the man whose totaalvoetbal had dominated a continent. Since then the Dutch had had their own nadir, missing the tournaments in 1982, 1984 and 1986, but were on their way back to prominence thanks to a talented crop including Van Basten, Ruud Gullit and Frank Rijkaard alongside older hands like Arnold Muhren and Wim Kieft.

However, in this clash of the styles it was the Irish who created the best chance, Paul McGrath rising to nod against the post from Ray Houghton’s corner — their only flag-kick of the game.

McGrath had been playing in midfield but relocated to right-back thanks to Chris Morris’s injury, and would have looked as just as home in orange as in green. But McGrath, and Ireland, were powerless against what must go down as one of history’s most fortuitous winners.

In the 82nd minute, a Dutch cross from Jan Wouters sailed over Van Basten and McGrath headed clear. It fell to Ronald Koeman just outside the D, but the big blond shanked his volley into the floor. It was sailing well wide of Bonner’s right-hand post until Kieft, stood outside the post and 12 yards out, flung his head at it.

Kieft had done well to react, but the ball was going 15 yards wide of Bonner’s other post. Well, it was until it hit the ground, and physics took over. Some combination of Koeman’s shot and Kieft’s deflection had imparted such spin on the ball that it skipped up and lurched sickeningly towards Bonner’s goal.

The brilliant Irish goalkeeper reacted immediately, throwing himself toward the ball, but it was too near the corner and bumbled almost apologetically into the net. It’s a video to show to anyone who ever unambiguously uses the phrase “The Luck of the Irish”; it’s worth noting that the word “luck” comes from Middle Dutch, and on this day the Netherlands embodied fortune.

What happened next

The Irish fans were undaunted, singing their hearts out for the rest of the game and a full half-hour afterwards in the Parkstadion. Charlton would lead them to the knockout stages of Italia 90 and USA 94 and will never again need to buy a drink in a bar containing an Irish fan.

The Dutch would go on to win the tournament, beating their old rivals the Germans along the way and cultivating a confident generation who in turn inspired another major crop of young talent in the ’90s; by seamlessly incorporating them, the Oranje reached the Italia 90 knockouts, Euro 92 semis, USA 94 quarters, Euro 96 quarters, France 98 semis and Euro 2000 semis.

Originally published by FourFourTwo on June 18, 2016.