How the 1990s saved English football

In the 1980s, football was at an all-time low — but Gazza’s tears helped to usher in an era that saw the game return to its place at the heart of British popular culture. Gary Parkinson remembers the renaissance…

Nostalgia ain’t what it used to be. The word was coined in 1668 as a medical diagnosis, combining the Greek nostos (homecoming) and algos (ache or pain: see also neuralgia, ‘nerve-pain’). The neologiser was scholar Johannes Hofer, describing the homesickness of far-flung Swiss soldiers pining for the Alps.

Since then nostalgia has gone from being a treatable condition to a heritage industry, a lucrative revisiting not of place but time: “Remember when this happened?”. Sufferers are indulged but also mocked for living in the past, seen as Luddite heretics railing against the mantra of progress. Why live in the past when the future is inevitable?

One popular Golden Age theory has it that humankind is always pining for an era around 25 years ago. This neatly fits the average generation gap: as parents explain their experience to children, the new breed is permeated with a schismatic attitude which veers between hopeless romanticism and destructive iconoclasm.

History’s rarely neat, but the great dividing point seems clearer in football than elsewhere. Old Football gave way to Modern Football in the summer of 1992, with the simultaneous inauguration of the Premier League, rebranding of the Champions League and prohibition of the backpass.

The accelerated changes since then haven’t all been for the better, however. Although only an obstreperous few would argue that the world’s finest players should not earn well during their short careers, the trickle-down economics of post-Bosman wage structures have meant that football now devours a vast amount of money from its fans, via tickets, merchandise or pay TV.

Alongside the resentment is an understandable distaste for the idea that records began in 1992, a data-driven selective memory which at the same time legitimises the questionable founding motives of the Premier League and eradicates all that went before.

These and other problems lead to the catch-all complaint known as #AgainstModernFootball, an umbrella for the usual variety of worried citizens, reactionaries and young fogeys. In several cases, they’ve got a point. But as usual, the case is overstated when oversimplified and transmuted into its natural corollary: If Now Is Bad, Then Must Have Been Better. As New York Times writer Carl Wilson puts it: “Nostalgia tends to neuter critique”. Thus we find the 1990s reductively blamed for everything wrong with the modern world, by digital natives who were not around to witness what went before.

Nobody who attended games in the 1980s could sanely wish to turn back the clock and regularly experience it all again. Yes, the changes wrought by the ’90s were commercial but they were also cultural and social, while creating big advances in communication, entertainment, quality, availability, accountability and choice. The decade accelerated our sport from a despised primitive minority concern to this planet’s finest lesire pursuit.

What follows, then, is not a denigration of what went wrong, rather a celebration, and an explanation of how and why the ’90s made the game we love so much better than it used to be. And for that, we need to go back to the late-80s to see how bad it had become.

Unacceptable in the ‘80s

You are scum. You are assumed to be a criminal, if not in deed then in intent. You are herded, like cattle to the slaughter, from heavily policed railway stations to crumbling, uncovered terraces or ancient stands in which you are hemmed in by lethal fences.

Socially, your hobby makes you a pariah. Most people do not recognise football as a suitable topic for conversation, knowing it mostly from the scare headlines about hooliganism, and ignorance breeds contempt. Revealing your inclination unlocks a series of assumptions about your background and personality.

It might sound exaggerated but this is how football fans were perceived. In 1985 — the year of Heysel, the Bradford disaster, the Luton-Millwall riot, of English teams being banned from European competition — The Times described the game as “a slum sport played in slum stadiums and increasingly watched by slum people”. And this wasn’t an unusual opinion; many would merely alter “slum” to “scum”.

As the economic hardships of the ’80s continued to bite, the football fan became a lightning rod for societal ills. 1985 was also the year of riots away from football stadiums — in Brixton, Toxteth, Peckham and Broadwater Farm. But somehow it was all football’s fault. When Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher hauled various dignitaries to a №10 crisis summit after Heysel, she asked what football was going to do about its hooligans. Football Association chief Ted Croker dared to challenge the Iron Lady: “These people are society’s problems — we don’t want your hooligans in our sport, Prime Minister.” Croker became the first FA secretary in a century not to be knighted.

The assumption that football supporters were hooligans-in-waiting became ingrained. The Thatcher government’s attempts to introduce compulsory ID cards were only shelved after the outcry following the 1989 Hillsborough disaster.

The resultant Taylor Report ended the medieval conditions inside the grounds but, just as importantly, British society acknowledged it had been treating a subculture as an underclass. Having had its ultimate low, it was time for football to start looking up.

Around the same time, incidences of hooliganism waned sharply — particularly at matches. Those in search of combat thrills might still meet up for a tear-up, but it tended to happen away from the ground and away from the public gaze, which was just fine by the real fans. To the amazement of amateur sociologists, it turned out a generous proportion of the ‘hooligans’ were simply bored middle-class blokes emasculated by their office jobs. Strange how they never mentioned it at cocktail parties…

Meanwhile, a small but still influential number of supporters on the terraces were having their brain chemistry changed by a popular new street drug: it’s difficult to kick off a riot when you’re mellowed out by Ecstasy. Following the Second Summer of Love in 1988 and the rise of Madchester in 1989, New Order had wanted to call England’s official Italia 90 single E for England. The FA were not that naive, but World in Motion — widely lauded as the best football single ever — still contained some none-too-subtle references in “one on one”, while the words in the chorus (“Love’s got the world in motion and I know what we can do”) were hardly the stuff of Chopper Harris and Norman Hunter.

While it would be patent nonsense to claim that every football fan was suddenly necking MDMA like Smarties, the love drug’s growing popularity certainly helped chill the vibe. Herbal aromas often wafted over tightly-packed terraces. And hooliganism ebbed away.

In 1991, police predicted horror when Manchester United reached the Cup Winners’ Cup final in Rotterdam — but the tens of thousands of Mancunian followers of Bryan Robson and Shaun Ryder threw parties rather than punches. Similarly, trouble had been expected at Italia 90, especially when England were drawn with the Dutch, Irish and Egyptians on the island of Sardinia.

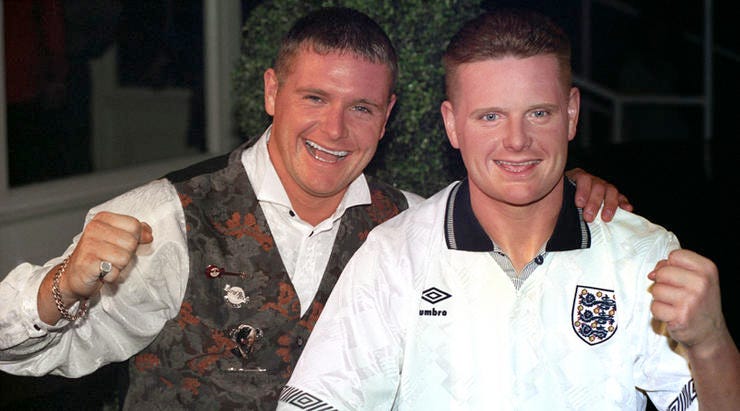

But instead of testosterone, the headline-making display of male emotion came when the team’s young star, Paul Gascoigne, cried on the pitch during the semi-final against West Germany, after an overenthusiastic challenge brought a yellow card that would rule him out of the final. It broke millions of English fans’ hearts, just as surely as the penalty shootout defeat that soon followed.

As the final credits rolled, the BBC’s theme music — Luciano Pavarotti singing Nessun Dorma — suddenly seemed entirely fitting for what had immediately gone before: a properly operatic tragedy, with the hero’s demise stemming from a fatal character flaw. In such circumstances, the aria’s thrice-repeated climactic word “Vincero” — “I will win” — only heightened the emotion.

Whatever their working knowledge of Italian, the wider English public fell hard for Gazza, and by extension for football. As The Guardian’s John Mulholland put it in 1994, “Gazza cried. The nation wiped away his tears and the media floodgates opened. Since then, coverage of football has seeped into previously unchartered territory: into the upscale literary magazines Granta and The London Review of Books; The Manageress has scored on television; thousands have enjoyed their Evening with Gary Lineker [a play based on the World Cup semi-final]; and tonight Opera North unveil their new soccer opera, Playing Away. The media deluge has been awesome.”

For Lineker, it “was a seminal moment”. “Lots of different kinds of people got interested in football, all different classes of people. It had a significant effect on the growth of football.”

Suddenly, we were no longer scum.

Here comes Johnny Foreigner

The ways in which the ’90s dragged football up from its nadir are many and various, but let’s start in the middle of everything: on the pitch. Anyone who thinks English football did not improve in the final decade of the last millennium needs their bumps felt.

Again, the comparison is with the late-80s. Banned from Europe and shunned by most compatriots, English football became insular. First Division clubs winning six consecutive European Cups around the turn of the decade hadn’t helped to dispel the notion that the denizens of Albion had nothing to learn from across the water.

As a result, overseas footballers — excluding the Irish — continued to be a rare species. Those who had been here were sporadic and exotic outliers like Newcastle’s Chilean siblings, “George” and “Ted” Robledo, broken-necked Bert Trautmann, Ossie and Ricky at White Hart Lane or erratic Villa winger Didier Six. The idea appeared to be that foreigners weren’t to be trusted to make their way through a muddy winter: the Wet Wednesday Night in Stoke is not a new concept.

There were some imports in the English game as the ’90s dawned, though they were few and far between. As an indicative example, the Arsenal 1989/90 squad contained just the one player born outside the British Isles — Icelandic bit-parter Siggi Jonsson, who’d spent five years at Barnsley and Sheffield Wednesday before moving to Highbury. Few Gooners were complaining: George Graham’s well-drilled yeomen had won the 1989 title in rather exciting fashion. But fewer still pined for those times after a decade of Arsene Wenger, Dennis Bergkamp and Thierry Henry. It was, safe to say, a bit better.

It wasn’t only Arsenal who benefited: just about every team decided that maybe we could learn something from Johnny Foreigner, and he was largely welcomed. Even the most zealous of xenophobes couldn’t carp when his side was immeasurably improved by a Gianfranco Zola, Georgi Kinkladze, Eric Cantona or Juninho. By the midway point of the decade, Champions League-winning strikers were joining clubs such as Middlesbrough, which is a bit like Watford bringing in Karim Benzema from Real Madrid.

Increasingly, the appreciation wasn’t merely parochial. The vast majority of the general public acknowledged that world-class players might be worth watching and incorporating. Drawing genuine admiration from around the ground, players like Ruud Gullit would be applauded off away pitches; even during the bitterest of derbies, fans at Old Trafford found themselves applauding the spectacular bicycle-kick attempted by some Leeds player called Cantona.

And increasingly these brothers from another culture encouraged our previously close-minded coaches to adopt new tactics: split strikers, trequartistas, ball-playing centre-backs, formations outside the standard 4–4–2. The game was evolving before our very eyes, especially with the backpass abolition making the game much more free-flowing.

There were some reactionary voices raised against the new arrivals. Cantona’s cross-Pennine move was met with Little Englander disdain in some quarters. Emlyn Hughes, writing in the Daily Mirror, said that the Frenchman was a “flashy foreigner” and a “panic buy”, who could “either win Alex Ferguson something this season, or cost him his job”.

In the event, he won Fergie a fair few things: four titles in his five seasons, the exception coming during an enforced lay-off following his overly enthusiastic meet-the-crowd session at Selhurst Park. Even that event, causing headlines around the world, proved how huge Cantona and the Premier League had become. By welcoming the world, the English top flight was on its way to becoming the globe’s pre-eminent league.

Reach for the Sky

Stars accumulated because Sky speculated. The story of Rupert Murdoch’s huge gamble — popularising his bin-lid TV start-up by ring-fencing live coverage of Premier League football in return for a then stratospheric £304m (the previous exclusive deal had cost ITV just £44m) — is well-known. Sky’s influence is also both divisive and intrusive: ask anyone who’s schlepped to and from a rearranged kick-off, or watched his or her lower-league side’s only half-decent player get plucked away to rot in a big club’s reserves.

But it’s worth going over a few of the benefits and ruling out a few half-truths that appear to have hardened into dogma. First, Sky did not “split” football. The FA did that thanks to its 1991 Blueprint for the Future of Football — advocating a breakaway league following a century of fiscal solidarity. Designed to wrestle control away from the Football League, the Blueprint was quickly approved by the bigger outfits who had helped to guide it, knowing they could guarantee a greater share of the earnings.

Nor did Sky ignore the rump of the Football League. As early as 1995, Sky outbid ITV for the rights to what was then the Endsleigh League, and they also picked up the pieces when the March 2002 collapse of ITV Digital threatened to bankrupt many lower-league clubs.

That wouldn’t have been necessary had the Football League chosen to accept a 1995 offer from the Premier League to grant the 72 clubs between 20% and 25% of any future joint TV deal in perpetuity. Instead the Football League opted to go it alone with a much weaker hand. The most recent live deal — Sky again — is worth £180m a season; 20–25% of the Premier League contract would have been worth more like £428m.

What Sky did for English football was to make it rich. This attracted far better participants, and eventually the cream of the global market. These players enriched the product, in turn making it more desirable and sellable. Besides, while largely footing the wage bill, Sky serviced you, the football consumer. Before Sky, apart from on the morning of the FA Cup final, there was no in-depth coverage: a weekly episode of Football Focus was as good as it got.

Even live games were pitifully bookended by minimal analysis. Check out YouTube (below) for the clash between Norwich and Manchester United in 1989/90, televised live on The Match. The chucklesome intro graphics make way to reveal the two teams coming out onto the pitch, leaving less than four minutes before kick-off. In that time, sheepskin-coated pitchside host Elton Welsby allows guest Graham Taylor literally eight seconds on the mic before sending him to the gantry while Brian Moore runs through the teams.

Perhaps wary of dedicating too much time from their schedules, the terrestrial TV channels were notorious for short-changing supporters. Sheffield Wednesday’s fanzine War of the Monster Trucks was named after the programme for which Yorkshire TV curtailed coverage of the Owls’ 1991 League Cup Final celebrations.

By contrast, Sky had time and space to give each live game plenty of build-up (two hours!) and analysis. Moreover, they quickly did it better than anyone else in the business, while always displaying a willingness to improve the ‘product’.

As a specialist channel, Sky could also allow for a much higher level of assumed knowledge. To hit a mass audience on ITV, explains Clive Tyldesley, a commentator “must communicate with the back row of the class”; a sports channel can expect a little more savvy. In its own way, this helped to grow the intelligence of the audience: we were no longer being ‘dumbed down to’.

Sky Sports managing director Vic Wakeling briefed commentary duo Martin Tyler (himself a former forward for non-league side Corinthian Casuals) and Andy Gray to “tell me the things I don’t know that only a player would”. This subtle advice raised the bar for in-game analysis, while the passionate Gray and smooth Tyler proved the perfect pairing for the big games.

Away from live coverage, Sky had acres of schedules to fill and proceeded to do so with ancillary programming. To begin with there was an awful lot of WWF, golf and the Bruno Brookes-hosted fishing show Tight Lines, but new output started appearing. Gray’s Boot Room provided in-depth tactical discussion via the medium of the Subbuteo pitch, while Friday-night debate show Hold the Back Page brought together Fleet Street’s finest well before they had to pretend to be sitting in Jimmy Hill’s kitchen for Sunday Supplement.

By 1994 there was enough content for the launch of Sky Sports 2, and Soccer AM debuted the following year. Afternoon-filler Soccer Saturday and hangover remedy Goals on Sunday both arrived in 1996 — the same year as Kevin Keegan’s “I would love it” post-match rant at Richard Keys — and in 1998 along came Sky Sports News with its hours of rolling reports, interviews, speculation and (eventually) Deadline Day reporters being assailed with giant pink sex toys. It’s all a long way from Elton Welsby.

Meanwhile, in Italy…

Before Sky dominated, there was a surprise hit from a left-field artsy channel which had barely even noticed football previously. It was a success which both reflected and encouraged fans’ awareness and appreciation of world football, not through hipsterism but genuine enthusiasm.

While TV production company Chrysalis were filming Paul Gascoigne’s recuperation from his FA Cup Final knee-knack, the injured party noted that it was a shame nobody in Britain would be able to watch him play for Lazio. A lightbulb quietly popped into life, Chrysalis bought the rights to Serie A’s UK coverage and sold them to Channel 4 for £1.6m: a live game per week plus the Saturday morning preview show Gazzetta Football Italia. (Later came Mezzanotte, a highlights package aired late on Sunday and midweek evenings.)

It was supposed to be hosted by Gazza, but that plan was quietly shelved when they realised quite what a loose cannon he was. For just one illustrative example, at Bisham Abbey on England training duty in October 1992, he was approached by a Scandinavian camera crew and asked if he had a message for Norway. Calmly addressing the camera, he responded: “Yes. F*** off, Norway.”

Boldly but ultimately wisely, Chrysalis instead promoted their researcher James Richardson to the front of cameras. It worked brilliantly. With the urbane but approachable Richardson — who had learned the lingo to converse with a Roman inamorata — sipping his coffee outside an Italian cafe, gesticulating at his mysterious pink newspaper, Saturday’s Gazzetta performed a double function: as a primer for those who didn’t know Serie A’s dramatis personae, and as an update for those who did.

“Italian football was huge back then,” Richardson has noted. “We’d just had a World Cup in Italy and it really captured the imagination. This was football in many of the same locations, a lot of the same stadiums. It was also a league which featured three members of that English team [Gascoigne, David Platt and Des Walker]. For anyone who enjoyed Italia 90 it was almost like a spin-off series.”

Indeed, Serie A’s 1992/93 season had some big names, and not just in the traditional Italian stronghold of defence. Milan had the Dutch trio of Marco Van Basten, Ruud Gullit and Frank Rijkaard; Ruben Sosa banged in 20 for city rivals Inter; Juventus alone could choose between Gianluca Vialli, Roberto Baggio, Paolo Di Canio, Fabrizio Ravanelli and Pierluigi Casiraghi up front; also among the goals that season were Gabriel Batistuta, Jean-Pierre Papin, Gianfranco Zola and Roberto Mancini.

These stars were paraded in the live Football Italia match in the Sunday afternoon slot suddenly vacated by the top flight’s commercial exile to the extraterrestrial; the Skyless audience who had grown accustomed to nearly a decade’s live Sunday service simply switched to Serie A. It helped when the first live game, between Sampdoria and Lazio, ended 3–3.

Football Italia soon had more than three million viewers, for whom Channel 4 had paid around 50p each; meanwhile, some Premier League matches on Sky — who had paid £304m for a five-year contract — struggled to attract as many as 400,000. (As broadcasters have found recently, the appetite for live football is far from insatiable. A few years into the new millennium, an ITV Digital game between Nottingham Forest and Bradford attracted just over 1,000 Thursday-night viewers.)

“The show was something of an anomaly at the time, a novelty to have a foreign league broadcast on British TV,” Richardson says. “It seemed exotic and I guess there was a real glamour compared to a lot of football people had been watching. For a lot of young and impressionable people, myself included, there was a romance to it. Everything seemed better back in the ’90s.”

Bants and Britpop

As the decade progressed and football became more popular, it found other niches in the television schedule. From 1991 to 1994, BBC Two’s ‘yoof’ producer, Janet Street-Porter, sanctioned four series of Standing Room Only — an entertaining attempt to make a TV fanzine. Touring the country’s grounds, its Supporterloo mobile studio gave fans a chance to vent opinions to camera. Guardian cartoonist Steve Bell produced a comic strip, Rory Bremner added voices, and David Baddiel and Rob Newman contributed comedy.

Chelsea supporter Baddiel then joined up with West Brom fan Frank Skinner for Fantasy Football League. Perfectly timed to surf across the mid-decade zeitgeist of Britpop, Loaded and laddism, the show oozed affectionate self-mockery — did anybody really care which manager’s fantasy team won? — while providing perfect post-pub entertainment.

In time for Euro 96, the hosts wrote and recorded vocals for a joint single with The Lightning Seeds. In contrast to every previous ‘football song’, the lyrics to Three Lions managed to strike the perfect balance between head-hung despair and misty-eyed optimism that generally characterises the fans’ experience. No wonder it went to №1, and did so again two years later ahead of the 1998 World Cup, with updated lyrics reflecting England’s latest near-miss.

Euro 96 was peak ’90s. Soundtracked by Britpop and a sociologically neat foreshadow of the impending New Labour revolution — high hopes of happier times, and eventual ennui or anger at things ending up the same as they always do. And with Scotland drawn in the same group, it also prompted England fans to start waving the George Cross rather than the Union Jack, a faltering first step along the road to a separate English identity and, arguably, the UK’s dissolution. Tony Blair’s 1997 manifesto included pledged referendums on a Scottish Parliament and Welsh Assembly, and the 1999 Good Friday Agreement created several institutions bridging the north and south of Ireland.

Back on the pitch, though, football was coming home. Redeveloped stadiums were buffed and polished, the flags fluttered expectantly and England played a blinder by demolishing the Dutch and battling past Spain, with Stuart Pearce enjoying the personal exorcism of his penalty demons at Italia 90 before reprising the ‘heroic losers’ routine from six years earlier.

In truth it was not the greatest of tournaments — the attendances were iffy everywhere but Wembley and the goal rate was low — but Euro 96 felt like a football party with Britpop banging on the stereo. It might sound trite, but it’s rather fun to stage an international tournament — it’s probably a sign of just how much the FA is despised around the world that despite the Premier League riches helping to build arguably the finest collection of stadiums on the planet, England have only been allowed to host one major tournament in half a century.

England’s semi-final exit from Euro 96 didn’t stop the momentum of what became known as Cool Britannia, though as is the way with fads, it quickly provoked a backlash. For a minute there, everything looked tremendously exciting. “Hindsight often judges the era unfavourably,” writes Michael Gibbons in When Football Came Home: England, the English and Euro 96. “But a generation that had emerged from the rubble of the 1980s in Britain helped to send an undeniable wave of optimism through the country. For a short while, anything seemed possible.”

Lobbing disdain from a distance, some pour scorn on the Britpop era — there’s a limit to anyone’s taste for inter-Gallagher squabbling and lager-vomit. The denser end of lad culture tarnished the whole with an ever-lower common denominator: boobs, booze and bants. It wasn’t always thus. Founding Loaded editor James Brown often highlights the fact that early cover stars included Gary Oldman, Airplane! star Leslie Nielsen and a young ‘Prince’ Naseem Hamed.

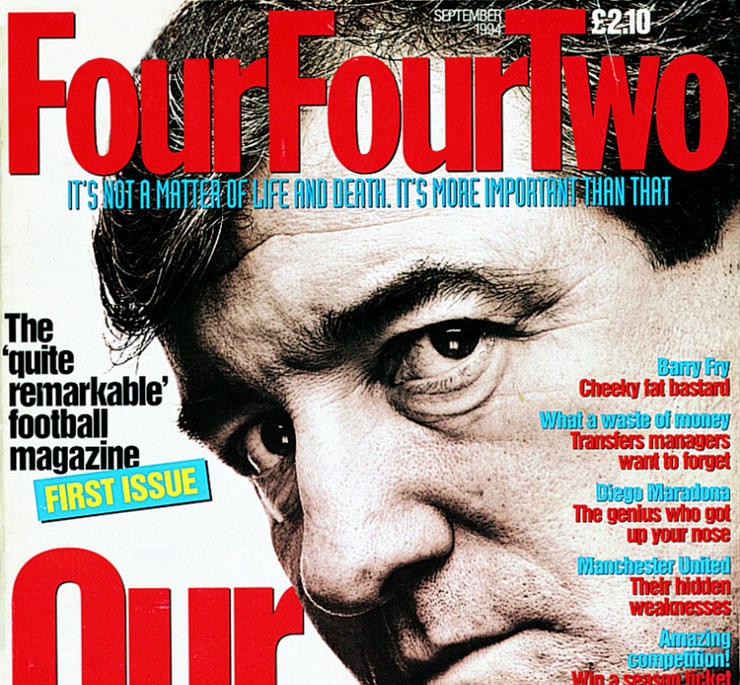

“I never thought Loaded was sexist at all,” stated one contemporary magazine editor, who happens to be a woman. “The writing was great, it was inventive and crazy.” The woman was Karen Buchanan, and the mag she launched was called FourFourTwo.

An alternative voice

The mighty organ you hold in your hands was first unleashed in 1994, shortly after the only postwar World Cup for which none of the Home Nations qualified (the decade wasn’t all sunshine and chocolate, but having a summer free from the binds of bias allowed a generation to become happily infatuated with Hagi, Stoichkov, Romario, Baggio and Bergkamp). Modesty prevents a full solo on the bugle of self-promotion, but FourFourTwo was always designed to appeal to intelligent, thoughtful, amusing, good-looking opinion-formers like you, and all the mates you’re going to persuade to subscribe.

Again, let’s flash back to the 1980s for comparison. Your choices, dear reader, are Shoot! or Match, which are fine unless you’re older than 13. There’s dusty old World Football, for those who love arcane league tables. And that’s about it.

But the new decade quickly brought salvation for the savvy older reader. From October 1990, with Gazza’s tears barely dry on his cheeks, you could enjoy 90 Minutes, a magazine set up in a Blackheath bedroom by Dan Goldstein and Paul Hawksbee. The affordable weekly’s irreverent nature was somewhat akin to Harry Hill’s TV Burp, in which Hawksbee was also involved.

As the decade wore on, other magazines appeared and disappeared: Goal lasted from 1995 to ’98, Total Football from ’95 to 2001, Match of the Day from ’96 to 2001, while 90 Minutes bit the dust in 1997. That left just three monthly magazines remaining on the newsstand: FourFourTwo, World Soccer and When Saturday Comes.

Established in the mid-80s, WSC had adopted the punk movement’s use of fanzines: self-published mags and used as a platform for views unmediated by the journalism industry, frequently hyper-local in focus. Fans leapt upon the idea, and fanzines flooded in to fill the gap in the market: in-depth coverage of single teams, not all of it positive.

Previously, the only writing about many small teams had come from trite match programmes or local press coverage neutered by the need to nurture good relationships with the club. Now, fans could read — and write — honest opinions about their favourite bunch of idiots. As Peter Hooton — later the lead singer of The Farm, but before that the editor of influential Scouse fanzine The End — says: “Fanzines gave people an outlet which they didn’t have at that time. Nowadays everyone has a voice on Twitter.”

The increasing depth and breadth of fanzines could be determined monthly by one of the movement’s forebearers, WSC. Its circulation peaked at around 40,000 in the early-90s, though it played a vital role in the cross-pollination of ideas by the simple but crucial provision of a fanzine directory. In the back of every issue it printed a nationwide list of titles and addresses. That list then expanded from 22 in 1988 to a double-page spread, and as fanzines multiplied — by some estimates, 600 titles came and (largely) went — the list became so big that it was split over three consecutive issues. Visiting supporters could now hunt down the home side’s latest issue, or order via the postal service. An underground network was later established, with echoes of the independent music scene: indeed, issues were often available in non-chain record shops.

Having come to prominence in the 1980s and dwindled as print concerns in the post-millennial spread of the internet, fanzines boomed in the 1990s thanks to the proliferation of desktop publishing programs such as PageMaker. Previously, most fanzines looked like the amateur productions they were — often annotated typewritten pages reproduced on photocopiers, having been put together using a process in which “cut and paste” meant using scissors and glue.

By contrast, the affordable availability of slick computer software, and the improving processing power of home PCs, meant fans could produce content to match, or even better, official output. This democratisation of the means of production allowed thousands of frustrated creatives to excel — for Sunderland fans, A Love Supreme was leagues better than the official programme.

Even after the advent of DTP, many fanzine aficionados (readers and editors alike) preferred the rough-and-ready look, but this just created more choice. Clubs now produced more than one fanzine: an enviably glossy mag like The Gooner alongside a typewriter-and-Tippex affair like The Arsenal Echo Echo. And whatever the end product, the editors were grounded in the full gamut of production: writing, commissioning, editing, illustrating, typesetting (of some sort or other), design (ditto), reproduction, sales, distribution and planning. Fanzines created a new generation of journalists, including this writer.

The 2001 launch of the Rivals.net platform — which was swiftly aped by Footymad.net and FansFC.com among others — allowed fanzines to move online en masse, supported by centralised advertising revenue. Not long afterwards, Blogger and Wordpress arrived to assist anyone with a keyboard and a viewpoint. The golden age of print fanzines was over, but from now on fans would never be silenced.

Fever Pitch flings open the doors

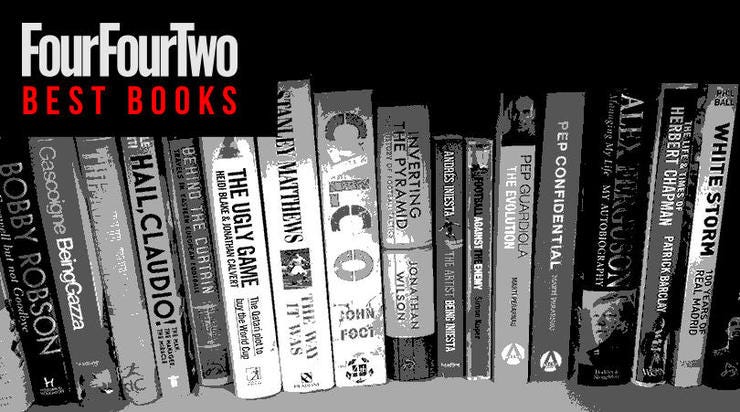

If the ’90s witnessed football writing spreading ever further across the breakfast table, it also made the huge leap to the coffee table and the bookshelf. Before 1990, most football books were just pulp nonsense: quick-buck memoirs or Christmas cash-ins. Notably, of FourFourTwo’s 50 Best Books, just five pre-date the ’90s.

Among the literati and book publishers alike, football fans were not expected to read much. In reviewing Bill Buford’s Among the Thugs for The Independenton Sunday in 1991, Martin Amis described fans as: “a solid mass of swearing, sweating, retching, belching sub-humanity” who “all had the complexion and body-scent of a cheese-and-onion crisp, and the eyes of pitbulls”.

Amis’s hateful tirade was an unarguably prevalent public view. When Saturday Comes writer Ed Horton labelled the review “class snobbery” and “a poisonous display of ignorance and bigotry aimed at the scum of the earth — you or I, the football fan.” He was correct, but the Amis rant — published in a new Sunday paper that was aimed squarely at the educated middle class — showed how acceptable it was to demonise football fans, and how low opinions of them had sunk.

“Prior to Italia 90, football in England was perceived as a squalid and hooligan-ridden embarrassing sump of gormless violence,” says Pete Davies. “You did not talk about it over dinner. Now it’s hard to go anywhere without people talking about it. It simply wasn’t a polite topic of conversation, as it was an embarrassment. Therefore nobody ever wrote about it — there was no such thing as a good football book back in 1989.”

Davies knows whereof he speaks, as nobody did more to effect that change. His seminal book All Played Out covered a 1990 tournament at which he’d been granted a level of backstage access unprecedented before or since. Although he wrote it in 56 frantic days in order to hit the Christmas market, this was no rush job: he had spent the year before the finals speaking to the players and manager.

Pete Davies had quickly earned Bobby Robson’s trust when the talkative boss blurted out that he was possibly going to drop Gary Lineker. This was tabloid gold (“You could get fifty grand for that,” Robson told Davies) but the author’s silence earned him the trust to gain all the access he wanted: pre-match, post-match, at hotels and training camps.

The players, too, trusted him enough to openly discuss the need for Robson to change his tactics. He also mixed with the press pack and their alter-egos, the hooligans. Lesser hands would have mixed those ingredients into a shock exposé, but Davies had higher ideals in mind.

“I wanted football to have a proper place in popular culture. I thought someone should say, ‘Not all of us are lunatics. We’ve got legitimate reasons for watching this game, which is incredibly important culturally and matters to everyone in the world.’”

Albeit helped by circumstance — Gazza’s tears, England’s heartbreak and Robson’s dignity — he succeeded brilliantly through his ability and, crucially, empathy. Not bad for a book that Davies had only started researching as an explainer for the American market, in an attempt to get a publisher to pay his way around USA 94. “The biggest sport on earth was a complete and utter mystery to them — I thought: ‘Let’s explain it to them’.”

That desire to elucidate the reasons for fandom drove the book, which in turn turbo-boosted football’s crossover into acceptable coffee-table conversation. Nick Hornby’s Fever Pitch was a pivotal reference for the non-believers, a book that took the game from the pub to the coffee table and helped millions to understand how we fans function.

Fever Pitch sold a quarter of a million copies within three years. John Gaustad, the former owner of the much-missed Sportspages bookshop in London’s Charing Cross Road, once said: “It transformed the game and persuaded a lot of publishers, who’d previously not been convinced, there was a market for an intelligently written book on football.”

In fact, the market already existed before Hornby or Davies. In 1983, Simon Inglis managed to convince a publisher into a 4,000 print run of stadium-architecture investigation The Football Grounds of England and Wales. Four years later, it was updated with Scottish additions as The Football Grounds of Great Britain. The two versions sold more than 120,000 copies — not bad for a fairly academic study published at the nadir of attendances: back in 1985/86, the average crowd among the 92 Football League clubs was 8,130 — a little over a third of the post-war peak of 22,333 in 1948/49.

New opportunities

But the crossover success of Fever Pitch flung open the doors, and as publishers scrambled from looking down their noses to looking at the possibilities, they found writers who were capable of contextualising football in everything from intelligent sociology (Simon Kuper, Football Against The Enemy, 1994) to vibrant local humour (Harry Pearson, The Far Corner, 1994).

Publishers could repackage the heritage works of supremely talented writers such as Hugh McIlvanney (McIlvanney on Football, 1994) and Eduardo Galeano (Football in Sun and Shadow, 1997). They could also commission new takes at legendary tales (The Robin Friday Story, 1998) and they could confidently distribute some niche works, such as Joe McGinniss’s The Miracle of Castel di Sangro (1999). Come the end of the decade, they could even pay Alex Ferguson a seven-figure sum for his autobiography. As usual, not everything they pushed to market proved to be gold or even good, but at least we crisp-faced, swearing, belching sub-humanity had the choice.

The Observer said that Fever Pitch caused “the emergence of a new class of soccer fan — cultured and discerning”, but that’s a somewhat arrogant dismissal of the fans who went before. Kuper was an Oxford alumnus roughly a decade after Hornby had attended Cambridge. Football had never been simply for the thicko plebs. It had always attracted followers of all intelligences and backgrounds — it just ceased to be a dinner-party bete noire.

As Kuper puts it: “Hornby didn’t get the middle classes involved in football, but he allowed them to talk about football in their books and newspapers.” Even so, the somewhat sudden embrace by society’s middle orders caused some resentment in the working-class bedrock. Kuper had noticed an attitude of “‘People shouldn’t write literate stuff about football, football’s an honest working-class game and all these Johnny-come-lately middle-class poseurs should get out.’ Nick Hornby got a lot of that, but it’s gone away now.”

Phone-ins fill the void

At the beginning of the ’90s, the radio played a prominent part in the travelling supporter’s life. Every Saturday teatime, faced with miles of mirthless motorway and an annoying wait of a few years before cars habitually sported CD players, away fans would religiously listen to as much of Sports Report as was left when they reached the motor from the terrace, and then… well, to start with, that was pretty much it. For the first year after its launch in August 1990, the new Radio Five (not yet known as “Five Live”) was a mongrel beast that covered the news, sport, education, children’s programmes and, from 6pm on Saturday evenings, The European Chart Show.

Clearly this was madness, and in ’91 they made an inspired signing — or rather, a tactical switch. A chatty Millwall fan called Danny Baker was proving popular on the lunchtime phone-in Sports Call, and so got asked to pop back from The Den in time to reprise the show just after the six o’clock news. Thus was born 606.

From the off, Baker was determined that this would not be a boring dissection of tactics. One topic on the maiden show, signposted ‘Just How Crooked Are Referees?’, attracted a call from Chelsea’s midfielder Andy Townsend, who was only too happy to reel off a few decisions from that afternoon’s match that he believed were questionable. As Baker notes: “Andy’s remarks made the Sunday back pages, and 606 was instantly declared to be the only place to go for all football fans when in transit each weekend.”

Baker’s bubbling stew of offbeat topics and rabble-rousing roped in a huge audience, who somehow were not put off when he stood down after a season to be replaced by David Mellor, a Conservative MP best known for a lurid tabloid splash detailing (falsely) how he’d persuaded his mistress to let him wear a Chelsea strip during sex.

The phone-in format was hardly new — one is mentioned in a 1925 edition of the Radio Times, and BBC Radio Sheffield had been hosting the football-themed Praise or Grumble for four years — but supporters flocked to put their two pennies’ worth across. The 1995 launch of Talk Radio (later refocused and renamed TalkSport) offered an alternative, and across the dial phone-ins proliferated — a prototype social media. As with any social medium now, at worst it can end up becoming bar bores shouting at each other, but at best it can provide some genuine insight and entertainment.

The ’90s also gave us video games that weren’t bobbins. Yes, some existed before — Dino Dini’s deathless Kick Off 2, various management sims — but in came the mega-franchises (Championship Manager first appeared in 1992, FIFA in 1993) and a variety of other games such as the popular Sensible Soccer.

Games also helped to broaden the minds. FourFourTwo contributor turned Blizzard editor Jonathan Wilson has suggested that the growth of supporters’ scope from parochial insularity to global awareness can be partly ascribed to the massive success of Football Manager. Sports Interactive studio director Miles Jacobson notes how: “When Hatem Ben Arfa signed for Newcastle and Alan Shearer said on Match of the Day that he’d never heard of him, loads of people went on Twitter to say: ‘He obviously doesn’t play Football Manager’.”

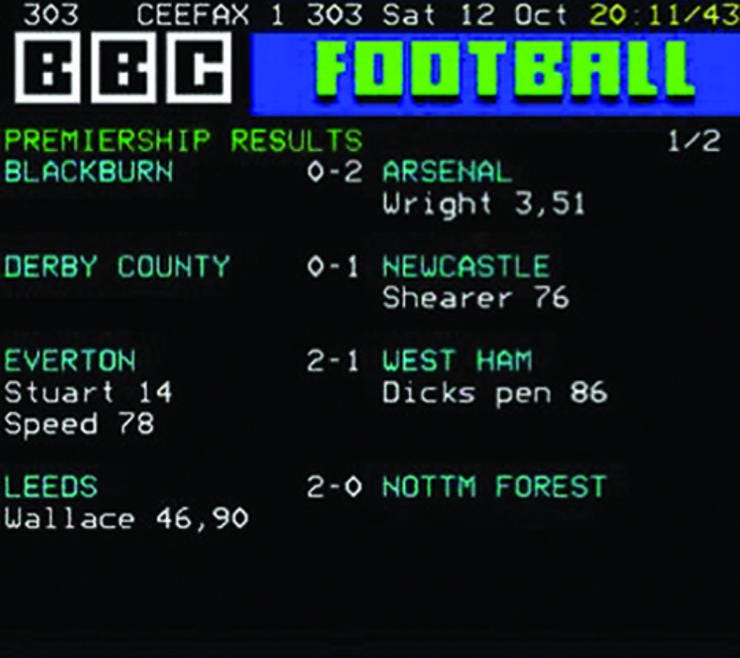

Ceefax, Ceefax, what’s the score?

If anyone ever says to you that “snackable content” is a new-media development, typical of a new generation’s short attention span etc, feel free to smack them over the head with a remote control. It’s now more than 40 years since the UK’s TV broadcasters started sending out 80-word bulletins — which told you all you needed to know.

Stumbled upon when technicians were trying to find a way to send subtitles over the airwaves, the BBC’s Ceefax service had launched in 1974. ITV’s service Oracle (Optional Reception of Announcements by Coded Line Electronics) was replaced in 1993, having been outbid for the franchise by Teletext. The limitations of the platform were obvious: no pictures, apart from ones laboriously formulated from alphabetical characters like a full-screen emoji. No video: a maximum of 24 lines on each screen, with a maximum of 40 characters per line.

If it sounds rubbish, that’s because it was, but if it was the best way of keeping in touch, that’s what you did. At the beginning of the ’90s, a phone was something that sat on a side table in your house and the internet was something you may have heard fleetingly mentioned on Tomorrow’s World. Though Radio Two might carry match commentary sometimes, sports stations didn’t exist on the radio, let alone TV.

So the best way to keep up with developing sports stories — like, say, latest scores — was to watch Teletext. On the BBC, you’d tap in 303 for the First Division matches and then be presented with alphabetised latest scores, split up over three pages (more as the pages clogged with the goalscorers and sendings-off). If your team’s score didn’t show up on that page, you just had to wait while the technology scrolled through, like a vindictive Vidiprinter. This mute, pixellated, bare-bones information was the way that millions of armchair fans discovered their team were going to Wembley, or getting relegated.

As the decade progressed, so did fans’ ways to keep in touch. Along came the internet, with the stuffy old Daily Telegraph becoming a surprise early adopter by founding the Electronic Telegraph (no, really) in 1994. Soccernet, set up with assistance from the Daily Mail, launched for the start of the 1995/96 campaign, and others soon followed suit, including the BBC’s website, the Mirror/PA joint venture Sportinglife.com and Football365, helmed by the former NME editor Danny Kelly and at one point valued at half a billion quid. And these sites began to reach wider audiences later in the decade, particularly around the time of the 1998 World Cup with the advent of minute-by-minute coverage.

But while primitive browsers such as Internet Explorer or Netscape Navigator might connect you to cyberspace via a dial-up modem, the information trickled towards you at a maximum theoretical speed of 56 kilobits per second, which was, in practice, usually more like 20kb. (For comparison, service providers now provide up to 300 megabits per second). And that was until someone wanted to use the phone, which shared the line with the modem: you couldn’t call someone and surf the Net simultaneously. And obviously there was no such thing as the mobile internet. What a time to be alive.

No, in the mid-to-late ’90s the average fan was more likely to keep abreast of football scores with a pager. Much more cheaply available than a mobile phone (which would not supply scores anyway, unless you expensively rang someone who was watching Teletext), a pager featured a single-line screen, across which would scroll score updates and latest news, provided for a subscription fee.

It was a very different time, and it brought rapid, seismic changes — football would never be the same again. Not everything new was to be applauded or welcomed, but the vast majority of it was. We had never had it so good, and to be alive in that time was heaven.

Its like may never come again, but its influence lives on forever.

Originally published at www.fourfourtwo.com on March 21, 2018, and before that (slightly abridged) as the cover story of the February 2018 issue of FourFourTwo magazine.