On this day in 1946: The Burnden Park Disaster remembered, by those who were there

In March 1946, dozens of fans were killed in a crush at Bolton. It was Britain’s deadliest stadium disaster, but lessons remained sadly unlearned

When Bolton Wanderers hosted Stoke City in an FA Cup sixth-round game on March 9, 1946, fans flocked to witness what they thought would be an unforgettable game. Sadly, that’s exactly what they got.

Bolton had won the FA Cup in 1923, 1926 and 1929, but had only got past the sixth round once since. They had won the 1945 Football League War Cup and hopes were high for more silverware. Stoke had never got past the sixth round (reached in 1928 and 1934), but they had the already-legendary Stanley Matthews.

Uniquely in FA Cup history, ties were two-legged in that first post-war season. The Football League hadn’t restarted, making the Cup more popular than ever.

Post-war excitement

Eyewitness Alf Ashworth attended the match with his brother Bill. “People came from far and wide because this was the first year the FA Cup was being played for after the war. People were coming back home from the forces, and Stanley Matthews for Stoke and Ray Westwood for Bolton — both internationals — were in the teams that day.”

The match wasn’t all-ticket: Bolton’s highest gate that season had been 43,453, well below the Burnden Park record of 69,912. However, Matthews’ fame added thousands to an attendance already swelled by Bolton’s 2–0 lead from the first leg, and the near-3,000 seats in the Burnden Stand were off limits, still requisitioned by the Ministry of Supply. In addition, the closure of the Burnden-side turnstiles for the huge Embankment end placed extra pressure on the entrances on the other side of the terrace.

Crowds started arriving in their thousands before 1pm, and by 2.30pm the Embankment was nearing capacity. Alf Ashworth could see problems developing from his vantage point at the other end of the ground.

Above: A view toward the Embankment and Burnden Stand

“Entrance was from Manchester Road only, and on the right by the turnstiles was a bar,” explained Ashworth. “People used to congregate round this bar, and wouldn’t move from there. To left of the goals there was a mass of faces and no spaces, while farther over it was evident that there was room, but people wouldn’t move over to the Burnden side of the ground.”

At 2.40pm the turnstiles were closed. However, thousands were still trying to get into the ground, and many broke into the Embankment from the railway behind it, removing sections of the ramshackle fencing. A concerned father and son escaped the crush by picking the lock of a closed gate, but once it was open thousands poured in.

Bill Cheeseman was on the Embankment with his sister, who had come specifically to see the great Stanley Matthews. “It was such a crush,” he recalled. “It was getting dangerous. We were getting squeezed by the people in front and behind. Everyone was pushing.”

Serious consequences

As the teams came out, a characteristic terrace ‘swell’ caused dozens to spill onto the pitch, temporarily holding up the game. By now women and children were being passed overhead to huddle at the side of the pitch, but this was not an uncommon occurrence at the time, and the game kicked off — with tragic consequences. As the crowd pressed forward again, two metal crush barriers gave way and the crowd collapsed in on itself.

“All of a sudden, those that were in front of us seemed to go –“ all falling down like a pack of cards,” said Cheeseman. “We managed to get out and I was glad about that.”

Others weren’t so lucky. Although play restarted, the seriousness of the situation was obvious even to Alf Ashworth at the other end of the ground. “People were being carried away on stretchers,” he saw with horror. “Some of them had their arms dangling over the side, and I thought they looked dead.” A police officer ran on to the pitch to alert the referee, who took the sides off the field at 3.12pm.

Half an hour later, on police instruction, the match restarted with a hastily constructed new touchline made from sawdust; beyond it lay bodies on makeshift stretchers, covered with coats. At half-time the players simply swapped ends and kicked off again, and the match ended in a goalless draw.

The players were unaware of the scale of the disaster. Stanley Matthews himself later wrote: “In our dressing room we heard more rumours about the increasing number of casualties. Yet it was not until I was motoring home that evening that the shadow of grim disaster descended on me like a storm cloud.”

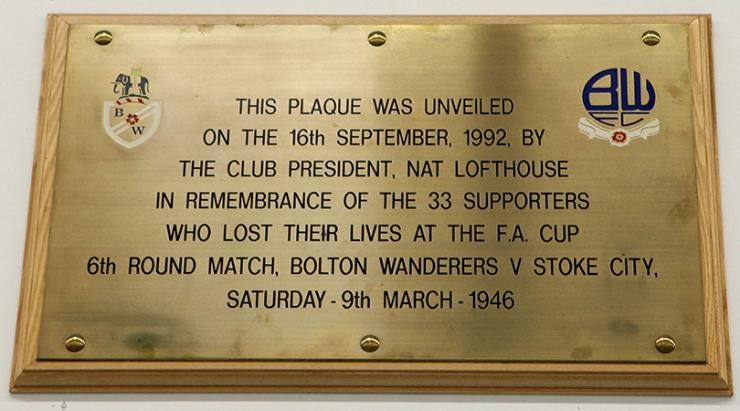

Thirty-three football fans had died and more than 400 were injured in what was then football’s biggest disaster. As Alf Ashworth asked: “Who would have thought that going to a football match would result in such a tragedy?”

A fortnight after the disaster, in the semi-final at Villa Park, Bolton lost 2–0 to Charlton — but they lost much more than a game that fateful March.

Originally published by FourFourTwo on March 9, 2017.