Why is the UK considering creating off-shore asylum centers?

The UK government has been discussing ideas for an immigration shake-up which reportedly include sending asylum seekers 4,000 miles away to camps on islands in the Atlantic Ocean, or holding them on ferries or decommissioned oil rigs. What are the ideas floated so far, why have they been suggested and what has been the reaction?

What are the reported ideas?

The Financial Times reported that home secretary Priti Patel had asked officials to explore the construction of an asylum center on the volcanic island chain of Ascension and Saint Helena, a British overseas territory in the Atlantic, 4,000 miles away and closer to Cape Town and Rio de Janeiro than to London.

The Daily Mail reported that officials were considering building detention centers on islands including the Isle of Wight off the southern English coast, the Shetlands off north-eastern Scotland or the Isle of Man in the Irish Sea.

Other ideas at a Whitehall brainstorming session reportedly included mooring a 40-year-old ferry off the English coast to house up to 1,400 newly-arrived asylum-seekers in 141 cabins, or sending migrants to decommissioned oil rigs in the North Sea.

The Financial Times said officials had even discussed the possibility of deploying boats into the English Channel, linking them together to form a barricade – or to use pumps to generate waves, to force small boats back into French waters.

What has been the reaction?

Opposition politicians and human rights groups have called the ideas "unconscionable" and "dismal" while academics have warned they would be expensive and impractical.

Speaking about the Ascension scheme, the opposition Labour Party's home affairs spokesman Nick Thomas-Symonds said: "This ludicrous idea is inhumane, completely impractical and wildly expensive."

Scotland's First Minister Nicola Sturgeon tweeted that "any proposal to treat human beings like cattle in a holding pen will be met with the strongest possible opposition from me."

Refugee Action CEO Stephen Hale said: "The government's speculative plans to round up human beings and confine them to prison boats or camps on remote islands are inhumane and morally bankrupt… Britain is better than this. We need a fair and effective asylum system, based on compassion, safety, and the rule of law."

Agnieszka Kubal, sociology lecturer at University College London, said the proposals would be economically unviable and might contravene legal obligations around asylum. "The UK would be within the letter of the law but would be breaking the spirit of the international law," she said.

However, Conservative MPs for Kent, the closest English county to the continent, backed the search for new solutions. Gravesham MP Adam Holloway said the Home Office was "completely right" to want "some sort of deterrent" for asylum seekers, while Dover MP Natalie Elphicke said the government had been "clear they are going to take whatever action is necessary to put a stop to these small boat crossings."

What is the government's response?

The government has refused to specify the precise ideas under discussion, but readily confirmed it was "developing plans to reform policies and laws around illegal migration and asylum."

Prime Minister Boris Johnson's spokesman said "there is clearly an issue here which we need to address," and as the UK attempts to deter migrants making dangerous crossings from France to "prevent abuse of the system and criminality" it was looking at the immigration policies of "a whole host of other countries."

One of these may well be Australia, where asylum seekers on boats are detained in offshore centers on Manus, Nauru and Christmas islands. The camps have been condemned by the United Nations after demonstrations, hunger strikes and suicide attempts among detainees.

One of the policy's main exponents, Australia's former prime minister Tony Abbott, has recently become a trade adviser to the UK government. The Home Office declined to comment on reports that architects of the Australian system were advising the government, but the interior ministry's most senior civil servant Matthew Rycroft said "everything is on the table" for "improving" the UK's asylum system.

Is the problem getting worse?

It depends how you define the "problem." There has certainly been a spike in migrants using small and dangerous boats to attempt the relatively short crossing of the English Channel – an entry route that Home Secretary Priti Patel has vowed to close off.

Almost 7,000 people have reached the UK in more than 500 small boats during 2020. In the first 23 days of September, 1,892 migrants arrived that way – more than in the entirety of 2019. Analysts say the coronavirus-prompted lack of trucks and ferries reducing stowaway opportunities has led to organized crime groups capitalizing by offering dangerous people-smuggling networks.

Steve Dann, director of criminal and financial investigations at the government's Immigration Enforcement division, said boats were becoming "significantly overloaded" which "increases the risk significantly." However, it also reduces the price: Dann says a place on a boat is now around $3,500 as opposed to about $5,200 at the start of 2020.

Calling the crossings a "chronic and enduring" issue, National Crime Agency (NCA) deputy director Matthew Long said "a hardcore element of organised crime groups" run a "financial model to exploit vulnerable people." Long called on social media companies to do more, noting that although the NCA requested the removal of 1,300 accounts between April and June, companies refused to take down about 500.

Are boat crossings a big part of immigration attempts?

Bigger than they were, but still a relatively small section. According to Refugee Action, 35,566 asylum applications were made in the UK in 2019 – down from a peak of 84,000 in 2002. Home Office figures suggest that including dependents, more than 44,000 people applied for asylum in the UK (of which around 19,500 people were offered some form of asylum or protection in the UK).

Depending on which way you cut those figures, the 2019 total of around 1,900 boat people is approximately four or five percent of the asylum applicants. The UK is also far from the only place targeted by maritime refugees. In mid-August, when the UK total of boat-based asylum-seekers topped 5,000, the UNHCR refugee agency noted that there had already been 16,942 sea arrivals in Italy during 2020, plus 10,875 in Spain and 8,697 in Greece.

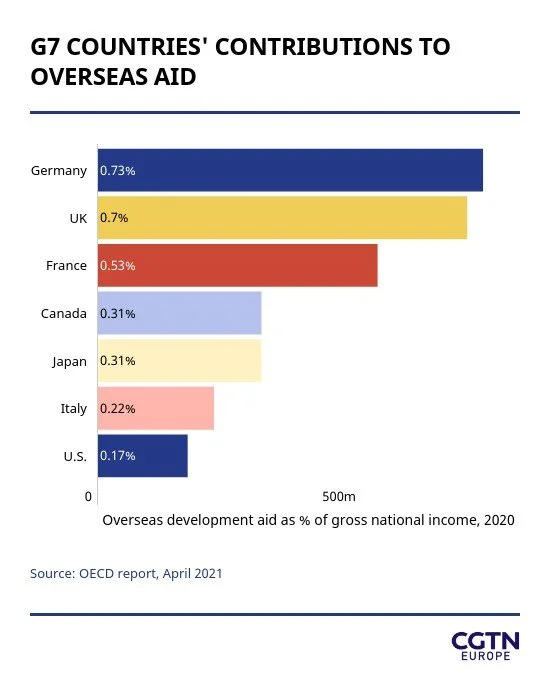

The 35,566 asylum applications to the UK last year represented a much lower number than applications to Germany (165,615 according to the EU office Eurostat), France (151,070), Spain (117,800) and Greece (77,275), while it's also worth noting the overall figure of 677,000 people immigrating to the UK in 2019.

The UNCHR's UK representative Rossella Pagliuchi-Lor noted that during the second quarter of 2020, overall asylum applications to the UK fell by 37 percent on the same period in 2019. In the year to June 2020, the UK asylum application total of 40,591 including dependents compared with 133,280 in Germany, well over 100,000 in both France and Spain and over 70,000 in Greece.

Pagliuchi-Lor said that "UNHCR will continue to advocate for an asylum system that is fair and compassionate," reiterating the agency's commitment to work with the Home Office to enhance the efficiency of the current asylum regime. That would not, by her preference, include any offshore centers.

"Processing asylum claims offshore has been proven to cause great suffering and come at a huge financial cost," she said. "Putting morality and costs aside, it would not absolve the UK from its legal obligations."