On the buses

Sit, listen and look.

Of late there has been something of a backlash against Yer Typical British Tourist. That’s understandable if YTBT is drinking a bathtub full of hard liquor and vomiting all over the pavement — and the boys are just as bad, etc — but there’s one typically touristy thing by which I steadfastly stand, and it’s the hop-on-hop-off sightseeing bus.

I recommend it for visitors to London — if not, there’s too much to learn aforehand, too much route-organising faff, too much to miss — and I advised it for family members who came to NYC last year. As they did it and enjoyed it, I took my own advice and hopped aboard. Here’s what I saw.

— — — — — — — —

William Randolph Hearst — he of the newspaper empire, the inspiration for Citizen Kane and the grand-daughter in the Symbionese Liberation Army — spied a site on Eighth Avenue and set about building a suitable HQ. It made it up to six storeys before the arse fell out of the market with the Great Depression, and it took 80 years to get any higher. When it did, it was this typically self-obsessed Norman Foster design, which now houses Cosmo, Esquire, Marie Claire and Harper’s Bazaar. Suitable, then, in that it’s all surface and no feeling.

Columbus sits atop his column in the middle of his eponymous circle. Behind him, Trump Tower.

Obligatory Times Square photos #1 & #2.

Madison Square Garden: It’s not square and it’s not a garden.

Opposite Madison Square Garden is yer neighbourhood post office. Its Corinthian colonnade was a polite response to the similar but monumental facade of the Pennsylvania Station, which sat majestically opposite it until 1963 — when it was torn down. There were protests, but as a dismayed New York Times editorial put it, a “city gets what it wants, is willing to pay for, and ultimately deserves.”

The Empire State Building opened in 1931, just in time for the Great Depression. Nicknamed the Empty State Building, it didn’t start well: in its first year it took as much money from the observation deck entry fees as it did from rent, and it didn’t turn a profit until 1950.

The Flatiron, the world’s first skyscraper, coolly demonstrates how not be hemmed in by circumstance. It’s famous for its shape and location, but it’s a looker up close, too.

The rather groovy Park Lane Towers, aka “The Jeffersons Building” after a 70s US sitcom. The story, as you ask, is that the former neighbours of Archie Bunker, who was the US version of Alf Garnett, have bettered themselves by moving from Queens to Manhattan. The twist is that they’re black. These things were important then, and they might still be important now.

Not sure what this one is, but if anyone wants to get me an apartment there, let’s talk.

After one thoroughly enjoyable bus tour, it took little persuasion to go back for another route as dusk fell. There’s something about a big city at night. Perhaps it’s an optical illusion, the built environment looming bigger in the frame once daytime’s azure infinity is replaced by the claustrophobic cloak of black. Maybe it’s the excitement (anticipation? fear?) that the denizens of the dark are on the streets. Or it may just be the childlike enjoyment of seeing lots of lights — an achievement of invention, industry and economics easily dismissed but still remarkable upon reflection.

If you can’t be excited by that view, then you’re very different to me.

Approaching the LCD maelstrom of Times Square.

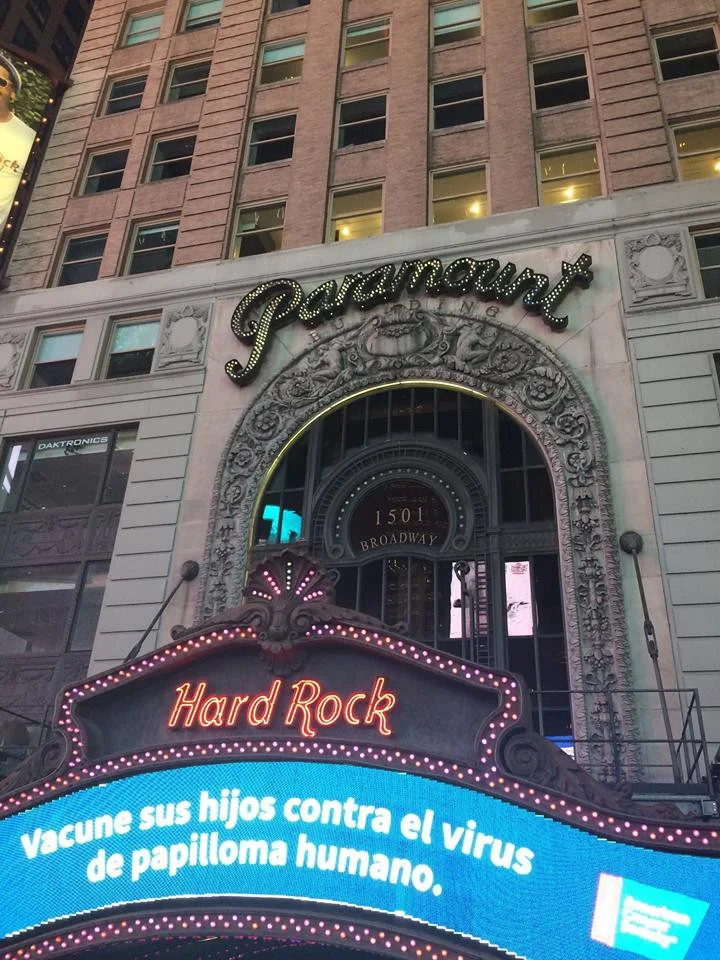

The Beatles played the Paramount in ’64. The stage is now part of a Hard Rock Cafe. Life goes on.

The Chrysler and Empire State buildings shoot gorgeously toward heaven.

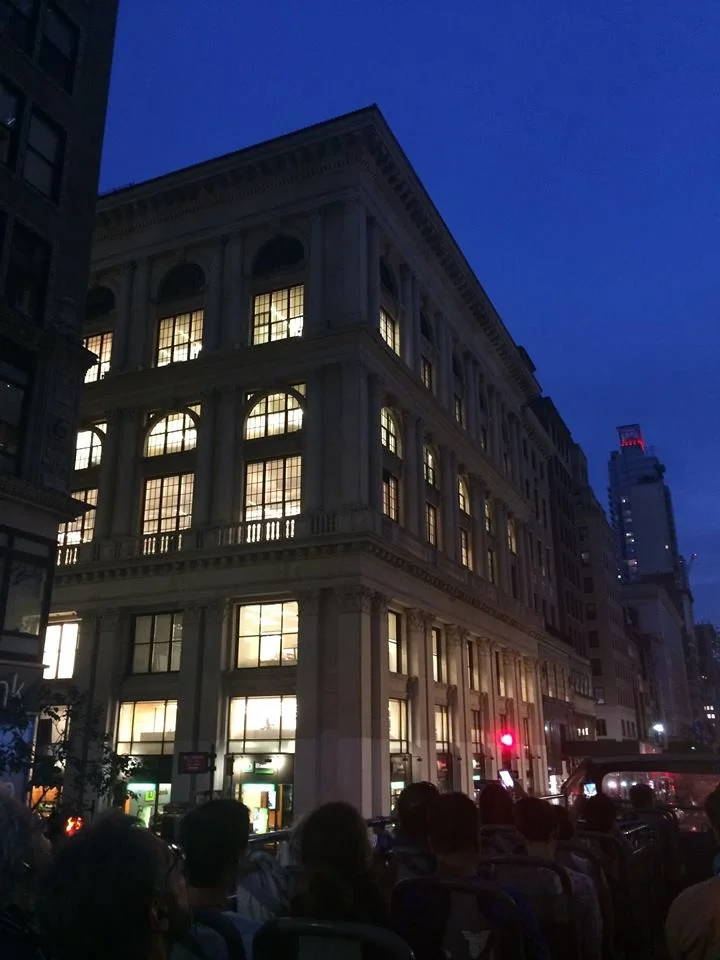

A city changes its clothes for the evening. Landmarks are lovingly lit, while facades previously overlooked can come into sharp-angled prominence. A neon nexus like Times Square bursts into a bright riot, but less obvious places suddenly look different. This photoset includes the Chrysler and Empire State buildings but also, between them, a less heralded structure; I couldn’t tell you what it is, and neither could Google Images (its best guess, winningly, was “building” — the march of the machines can wait awhile yet). In the daytime, you might walk past it without much of a thought; but at night, lit from within, its arched windows radiate intelligence and intrigue. Just another building, just another story, in a city stuffed with them.

The Brooklyn Bridge, shot at speed from the Manhattan Bridge. Manhattan may be the most famous of the five boroughs but Brooklyn feels more real. And not “real” as a euphemism for dangerous, not judging by the five separate young people (aged, I’d guess, between 15 and 25) who, a propos of nothing bar local pride, took the time to wave benignly at the embarrassingly obvious tour bus from which we gawked.

The new One World Trade Center looms showily above the Oculus, the entrance to a revamped transport hub. The transport hub was costed at $2bn but ended up costing a head-shaking $4bn of public money. That’s quite a ticket price for NYC’s 18th-busiest station, especially when you try it and it doesn’t really work: the various lines are long walks away, and it lacks boring essentials like clocks and maps (in desperation, staff have taken to sellotaping paper maps by the entrances).

Even the Oculus, the eye-catching overarching architecture (overarchitecture?) which rises above the station, is a fudge. Never shy of a statement, Santiago Calatrava concocted a glass-and-steel design supposed to resemble “a bird flying from the hands of a child”, with wings which would open or close depending on the weather. Security fears nixed that and stripped back his design so that it more closely resembles a beached whale two years into decomposition.

Just another building in Gotham.

Officially it’s 56 Leonard Street. To the public, including those who use it, it’s the Jenga Building. The tallest building in Tribeca at 57 stories (821ft, 250m), it was designed by Herzog & de Meuron as “houses stacked in the sky.” ‘Houses’ might be stretching it, but condo is a downmarket word and this place has upmarket pricetags: the cheapest residence (presumably the smallest, at 1,418 sq ft) was $3.5m and the top dollar was a $47m penthouse.

New York has inspired much fiction but the AT&T Long Lines Building at 33 Thomas Street could have come from the pages of George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four. A 29-storey skyscraper with no windows, it may be the high point of bald-faced brutalism. Technically a telephone exchange but rumoured to include mass surveillance, it was opened in 1974 having been designed to withstand a nuclear attack.

Its exterior walls are precast concrete panels, literally granite-faced. The only change from the monotony is a series of ventilation openings on the 10th and 29th floors. Completely self-sufficient, it contains its own gas and water supplies and can generate enough power to remain open for two weeks even without public utility input.